England’s traditional Big Six clubs have been in the limelight recently as news emerged of secret talks on changes to the Premier League’s governance in favour of top clubs: “Project Big Picture”

Hot on the heels of these reports were more leaks, this time on covert new discussions on a mooted European Super League, complete with lucrative revenue contracts and reportedly financed by JP Morgan Chase, to which five of Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, the Manchester clubs and Tottenham Hotspur would supposedly be invited.

Part of the Premier League’s appeal is its highly competitive nature – it is often said that on their day any team can beat any other, and even the safest of predictions are frequently upended. But in the third decade since the league’s formation a cluster of power clubs has formed, exemplified in the Big Six’s ultimately successful bid to ensure that revenue from the new international broadcasting deal agreed in 2019 to be divided up on the basis of merit, with teams at the top of the table receiving a greater share of the cash.

To establish whether there is a reasonable case for a separation of the Big Six, we looked into the extent to which these clubs are opening up clear water between themselves and the rest of the division. The Premier League is a famously competitive division on the pitch, but are these clubs creating longer-term advantages in commercial and financial terms that will make them unassailable?

A decade of dominance

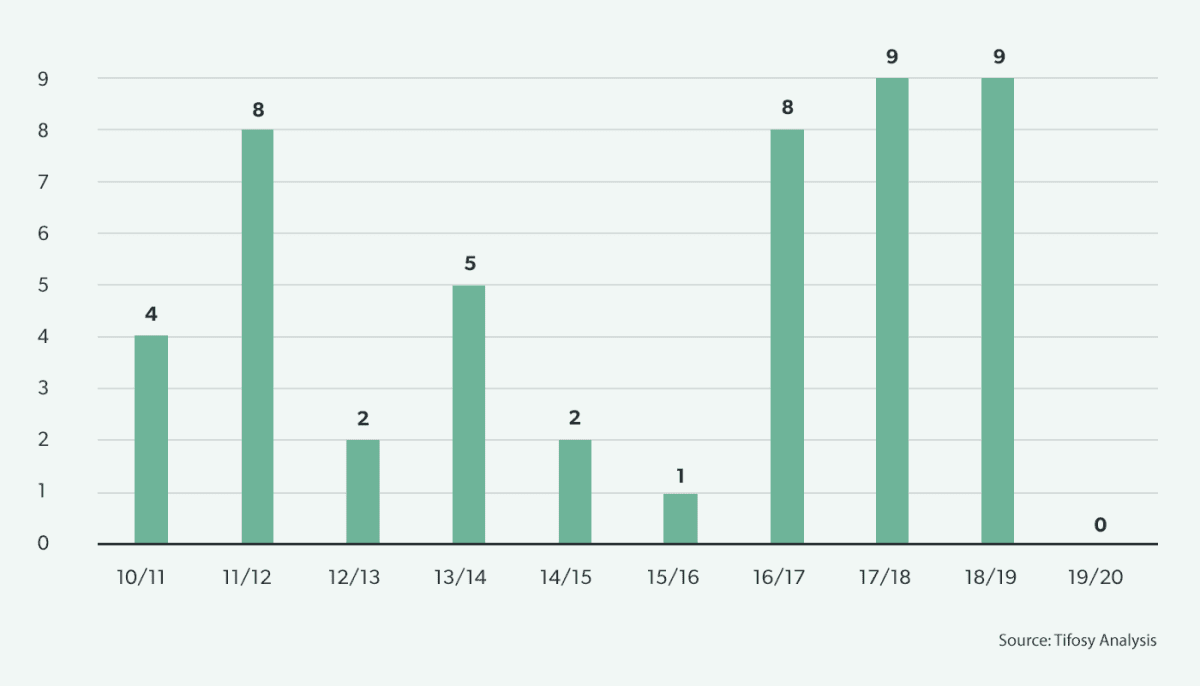

The holders of the six places in the Premier League is an exclusive club of clubs, with increasingly high membership fees. In the past decade, only one team outside of the Big Six named above has finished in a top-four position, when Leicester City shocked the football world (and beat 5000/1 odds) to win the title in 2015/16. Aside from Leicester City’s triumph, there have been only four occasions on which an “outsider” has finished in a top-six position: Everton twice (6th in 2012/13 and 5th in 2013/14), Southampton (6th in 2015/16) and Newcastle United (5th in 2011/12).

This dominance of the elite clubs can be further illustrated by looking at the points gap between the 6th and 7th league positions. On average the gap was 4.2 points in the five years up to 2014/15 and has increased only marginally to an average of 5.4 points in the last five years. But both 2015/16 and 2019/20 were very unusual seasons (though for quite different reasons) and from 2016/17 to 2018/19 the gap was between eight and nine points for three seasons in a row.

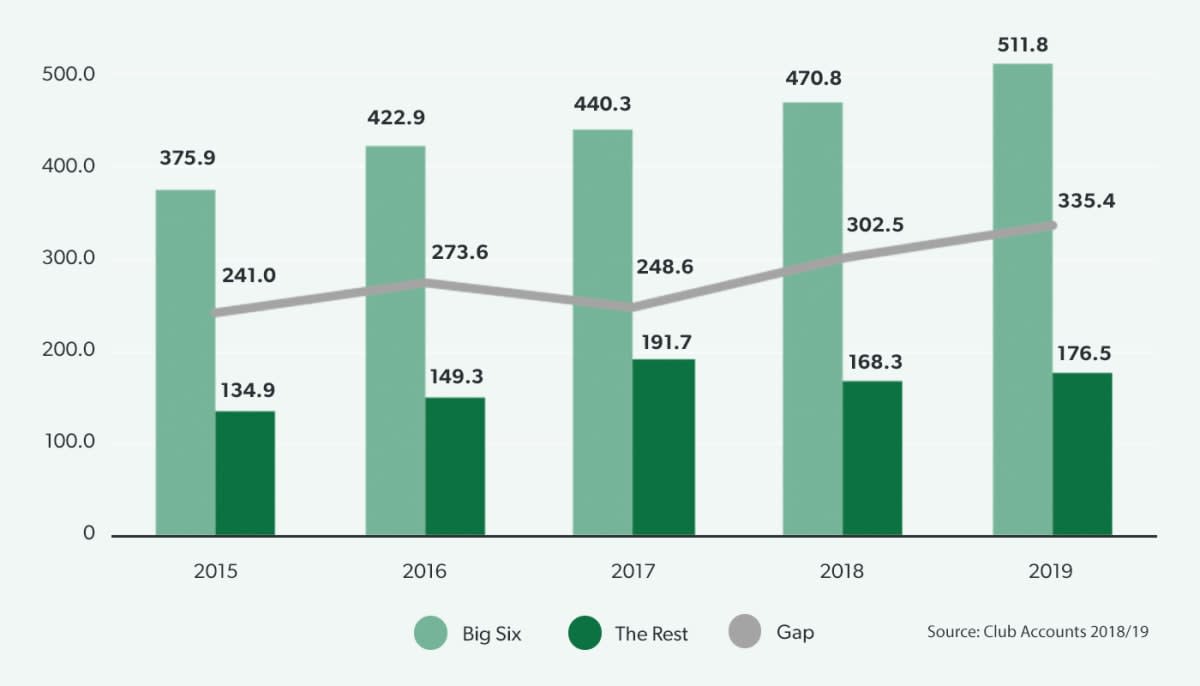

Revenue disparity growing, led by commercial

The gap between the average revenues of Big Six and “the rest” has grown 39% from £241m in 2014/15 to £335.4m in 2018/19, at which point the average elite club was generating revenues almost 3x the size of the average club outside of the Big Six. The trend was challenged briefly in 2016/17 when Leicester reaped the rewards – in broadcasting revenues – of winning the 2016 Premier League title and participating in the following season’s Champions League competition, but once “order was restored” in 2017/18 the gap continued to widen.

The trend is likely to continue – there are clear network effects in the football club commercial model as many revenue streams are built on consumer reach through digital platforms, where growth is directly correlated to on-pitch success and international investment, themselves enabled through the reinvestment of profits.

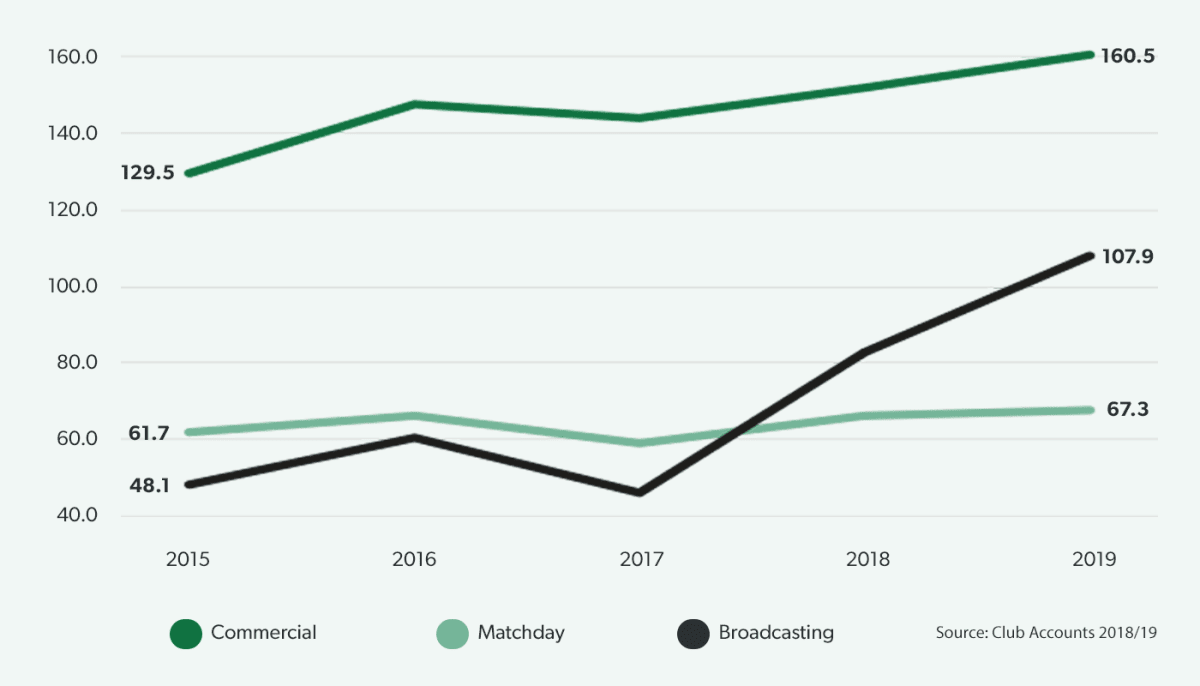

The biggest advantage is found in commercial revenues, where the difference between the Big Six and the rest grew from £129.5m in 2014/15 to £160.5m in 2018/19, an increase of 24%. Broadcasting revenues are becoming more important, however, as growing international distribution rights and UEFA competition prize money have increased the delta between the Big Six and the rest from £48.1m in 2014/15 to £107.9m in 2018/19, a jump of 224% - this despite the dip in 2016/17 as Leicester City qualified for the Champions League.

While they have been unavailable for the 2020/21 season-to-date, the revenue advantages arising from the use of a large, modern stadium are no less real in the long run. In 2018/19 average matchday revenues reached £67.1m higher for Big Six vs. the rest, an increase of 9% since 2014/15, with the twin effect of higher average attendances (56,028 vs. 36,965) and substantially higher average seasonal revenue per fan (£82.10 vs. £24.50).

No contest on social media

Social media reach (as well as that of a club’s website and email database) is increasingly vital in driving commercial revenues, as access to large global audiences is a key factor for sponsors looking to build their brands globally or in specific markets and, to a lesser extent, because these large audiences are a ready-made shopper base for online stores selling official club merchandise.

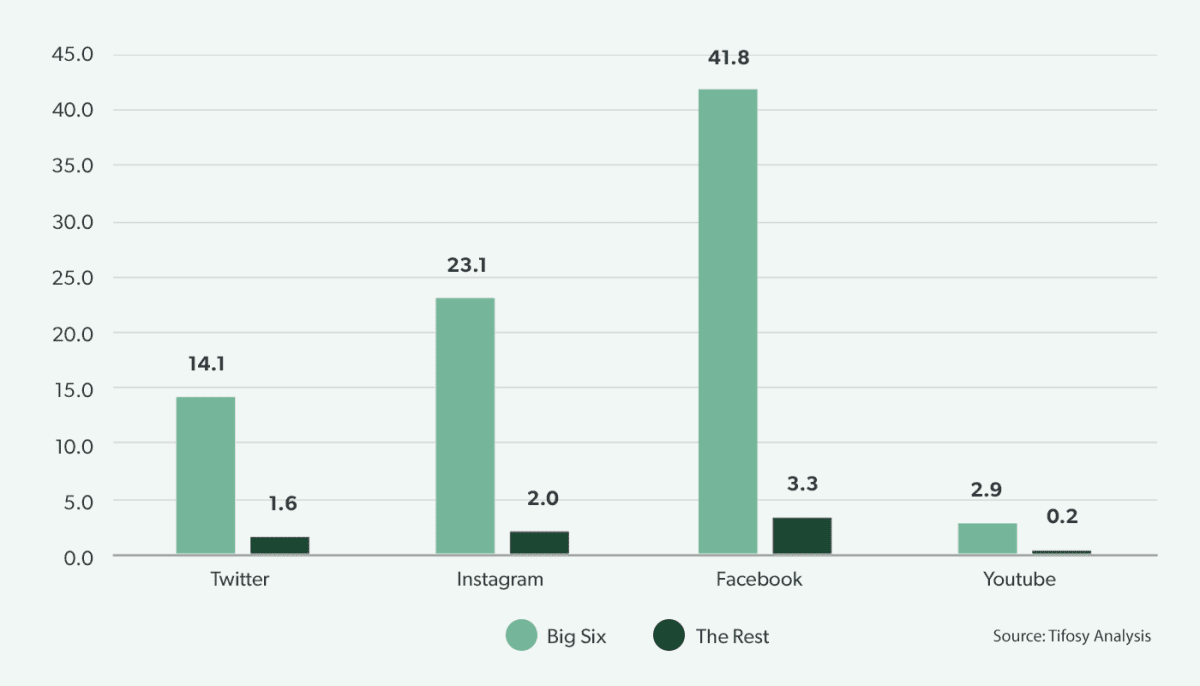

In terms of social media following, the Big Six tower over the rest of the clubs. Their average English-language Facebook (41.8m) and Instagram (23.2m) followings are more than 10x the rest of the league average, Twitter nearly 9x at 14.1m. Importantly, this only reflects the home audience. Big Six clubs host dedicated social media channels catering to an average of 6.5 additional languages – including Manchester City’s 11 languages and Tottenham Hotspur’s 9 – compared to just 1.4 on average for the rest of the league (e.g. Leicester City’s Thai Facebook page, Wolves’ Portuguese and Spanish Twitter pages and Sheffield United’s Arabic Twitter page).

Social media reach is increasingly vital in driving commercial revenues, as access to large global audiences is a key factor for sponsors looking to build their brands globally or in specific markets

Big Six outspending the rest

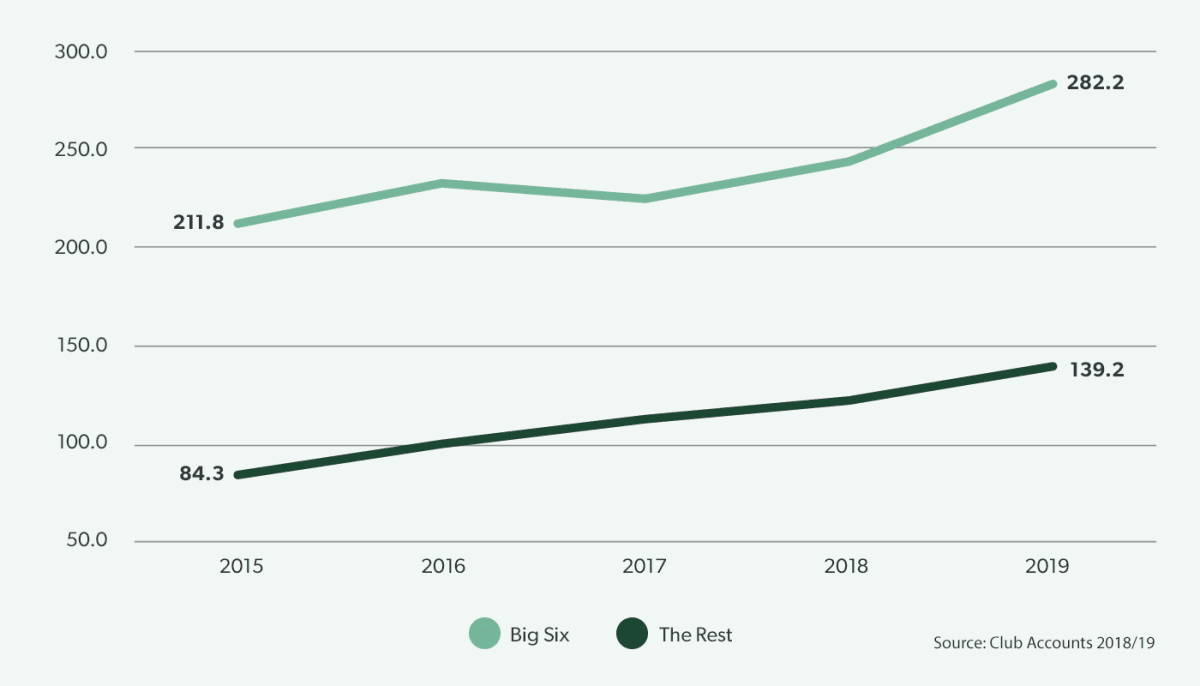

Clubs outside the Big Six appear to be starting to spend more each year in order to catch up with their larger rivals, growing their average wages by 65% between 2014/15 and 2018/19, against Big Six average growth of 33%. However, this growth rate reflects a lower base, and Big Six average wages stand at just over twice those of the rest in 2018/19, a gap of £143m.