Historically, Brazilian football clubs have been structured as non-profit entities constituted as associations, and are obligated to reinvest their proceeds back into the club. This meant that any previous investor would not be able to retain any part of the association’s profits, limiting the potential returns on investment.

However, the Brazilian government recently published a transformative ruling that changed the guidelines for the public registry of corporate entities. This ruling gave authorisation for the conversion of civil associations, including football clubs, into corporate entities.

As a result, Brazilian clubs are now able to establish football corporations, or Sociedade Anonima do Futebol (SAFs), which would transform them into limited companies. The law change aims to facilitate debt-burdened clubs to overhaul their ownership structure and stabilise finances. This also opens clubs up to external investment, the ability to issue bonds and would be subject to the regulations of the Brazilian Securities Commission.

Why do clubs need this change of regulation?

Following their first Copa Libertadores title in 2013, Corinthians was the 16th most valuable club in the world according to Forbes, worth over US $358m. Since their entry in 2013, no Brazilian club has subsequently entered the top 20, with lack of external investment and revenue diversification leaving Brazilian clubs trying to catch their European counterparts.

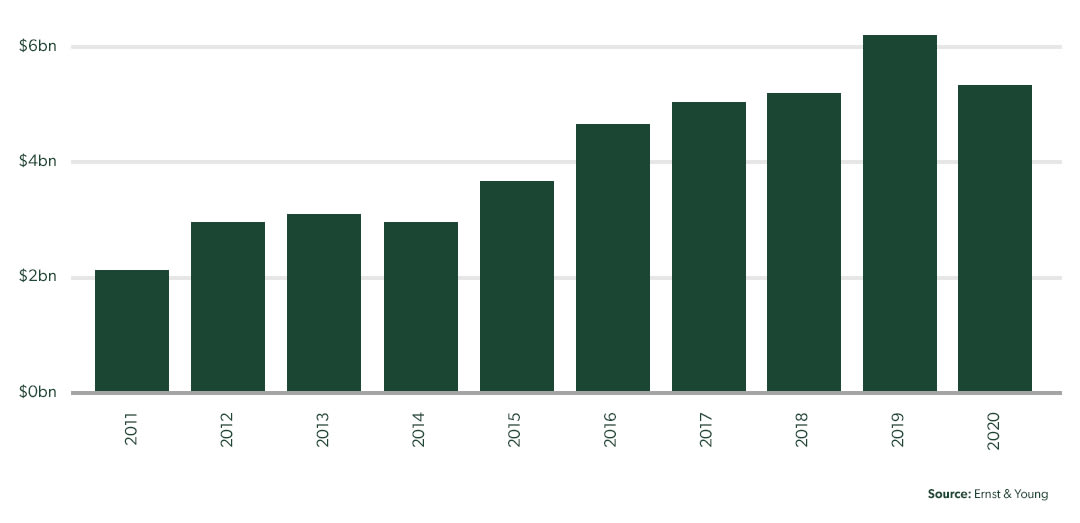

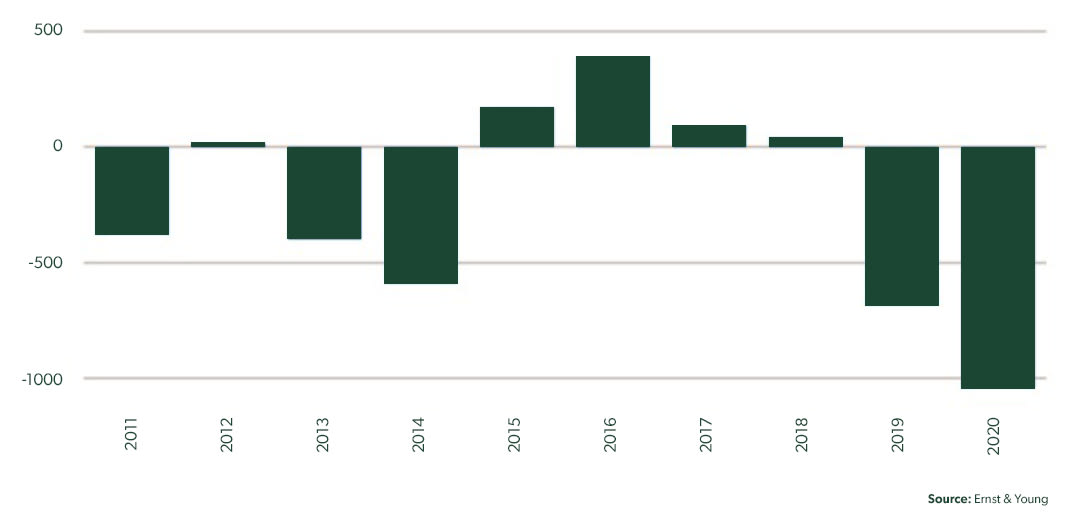

Despite continued growth in years previous, Brazil’s Série A clubs saw their combined 2020 revenues fall 14% year-on-year to R$5.3bn (US $998m), largely due to impacts from the Covid-19 pandemic. This decline was in line with European leagues, as the English Premier league (-12%), French Ligue 1 (-16%) and Italian Serie A (-18%) all recorded similar revenue drops.

In the same year, the revenue generated by Brazil’s largest five clubs (Flamengo, Atletico Mineiro, Corinthians, Palmeiras and Gremio) accounted for 56% of the overall total. Champions from that season Flamengo, made up 14% of that total amount of revenue on their own.

However, due to large amounts of debt and building deficits, it is believed clubs cannot sustain themselves to sufficient level to compete globally without investment. An Ernst & Young report, which analysed 23 clubs across Brazil revealed that combined net debt for 2020 stood at R $10.3bn (US $1.9bn), up 19% compared to 2019, demonstrating the need for additional investment.

Who has invested already?

There has already been a surge of interest, with many investors seeming to see an opportunity for high growth in Brazilian domestic football. Multiple deals have already been completed, while several further investments are also in discussion.

In December 2021, retired Brazilian World Cup winner Ronaldo bought a controlling stake in his former club Cruzeiro. Purchased through his Tara Sports company, he invested R$400m (US $70m) in the Belo Horizonte club, which has spent the last two years in Brazil's second division. This follows the 51% stake Ronaldo bought in Spanish club Real Valladolid in 2018.

In January 2022, US investment fund Eagle Holding led by John Textor completed a takeover of Campeonato Brasileiro Série A club Botafogo. The deal was signed ahead of Botafogo’s return to the top-tier following promotion from Série B last season. The takeover will see Botafogo take on the new corporate structure, selling 90% of its shares to Eagle Holding.

In the most recent transaction of this new wave of investment, 777 Partners have signed a Memorandum of Understanding for a 70% stake in Vasco da Gama. 777 Partners are paying R$700m (US $136m) for the stake. Including Vasco’s R$700m of debt, the deal values Vasco at R$1.7bn (US $330m), making it the largest transaction in the history of Brazilian football.

The deal is currently undergoing due diligence and awaits approval at Vasco’s General Meeting. Meanwhile, 777 Partners provided Vasco with a bridge loan of R$70m (US $13.7m), which will be converted to equity upon closing of the transaction. Vasco are the third club to receive significant investment post regulation change, signalling that more clubs may follow suit.

What potential are these investors seeing?

Transfer revenue potential

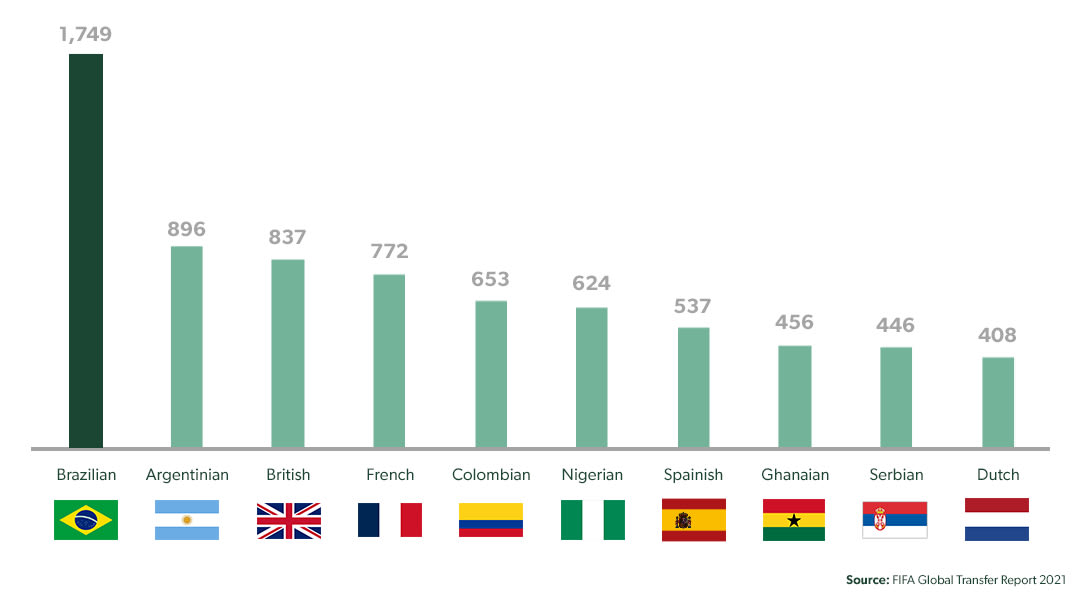

Brazil has a population of more than 215m and is home to the largest talent pool in world football. According to FIFA, there were 15,617 different players involved in international transfers in 2021, representing 179 nationalities. Brazilian players (1,749) made up 11.2% of total transfers, by far the largest group by nationality.

Brazilian players (1,749) were transferred more than any other nationality

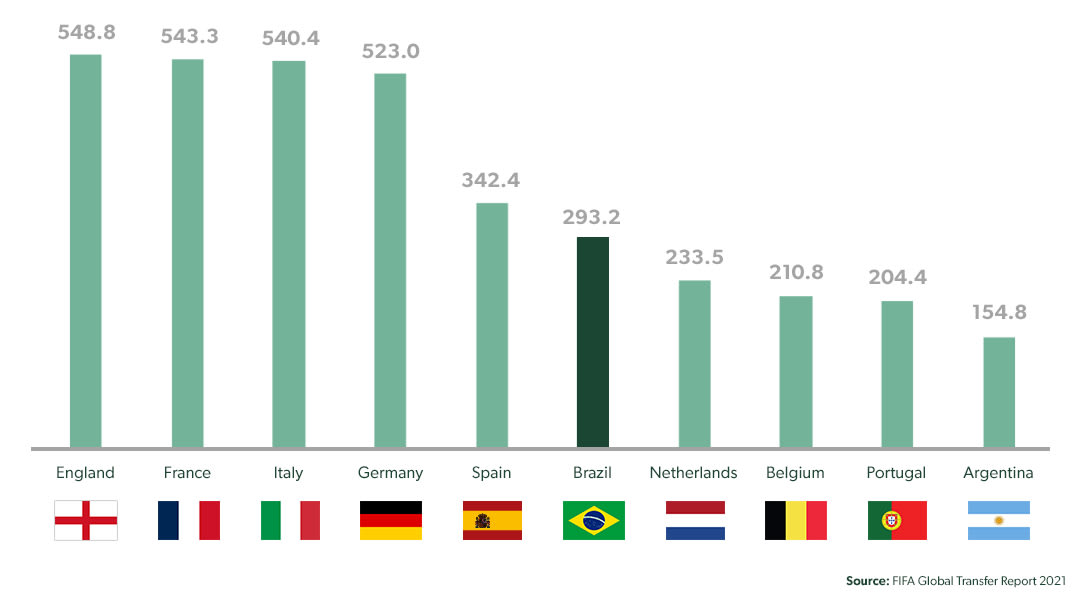

However, despite the vast number of Brazilian player transfers, Brazil ranks just 6th for transfer receipts (US $293.2m), significantly outstripped by their Big 5 European counterparts. The weight that European clubs hold in the transfer market ensures that premium prices are paid for their players, however this is not always true for Brazilian clubs.

Brazil ranks just 6th for transfer receipts globally

Although some high-profile Brazilian players have commanded enormous fees in recent seasons, this is often not put back into the Brazilian football structure. For example, in 2017/18 the transfer of Neymar from Barcelona to Paris SG (US $244.2m) and Phillippe Coutinho from Liverpool to Barcelona (US $148.5m), both Brazilian, equated to a combined US $392.7m. Despite a sell on clause of 5% in the Neymar transfer going to Santos FC and around 2.5% of the fee for Coutinho supposedly going to Vasco da Gama, most funds remain in European football.

Established fanbases in a country obsessed with football

Brazilian clubs command loyal domestic fanbases with enormous support across their country. The top clubs in Brazil have social media followings which contend with some of the top clubs in European football. For example, Flamengo is the most supported club in the country, with a combined primary social media following (across Twitter, Facebook, Instagram) which equates to 35m. This is around the same size as European giants Borussia Dortmund (35m) and exceeds Leicester City (15m) by almost 20m followers, although still a far cry from the likes of Barcelona (248m) or Manchester United (160m).

Out of the Big 5 European leagues, only the Premier League (6.3m) and La Liga (4.8m) have higher average Twitter followings than the Campeonato Brasileiro Série A (2.1m). With a much larger population base size in Brazil than European countries, domestic support is key for these clubs. Investors in Brazilian clubs will be looking to build upon this strong foundation, expanding support in overseas markets with the aim to increase club profile and commercial revenue.

Potential super league?

The potential for a breakaway league is also gaining momentum, with Brazilian top-flight teams plotting an independent future in search of billions in untapped revenue. The proposed breakaway league would replace Brazil’s current top-flight, Campeonato Brasileiro Série A, which some believe has struggled to match the best interests of its clubs and players due to oversight by the Brazilian Football Federation.

Multiple reports suggest a super league is edging closer, with a potential U.S. based private equity investment in the range of $750m and $1bn said to have been agreed. Sao Paulo FC president Julio Casares stated recently in an interview that “There have been failed attempts to realize a better league in the past” but “this time, the big difference is having a group of executives who come from the market with the experience”.

While an official breakaway has not been announced, the level of consensus is different from previous attempts. After the top division clubs agreed in principle to set up their own competition, 20 teams from the second division also pronounced themselves eager to be involved in what would be a new two-division setup. A reformatted league has the potential to provide considerably larger revenues for Brazilian football clubs, an opportunity clubs and investors do not want to miss out on.