Since the introduction of “Financial Fair Play” by UEFA in 2010, a lot has been written about the impact financial regulation has had on European club football.

Introduced following a 2009 UEFA report which showed that more than half of 655 European clubs incurred a loss over the previous year and at least 20% of clubs surveyed were believed to be in actual financial peril, the regulations were established to prevent professional football clubs spending more than they earn in the pursuit of success, and in doing so getting into financial problems which might threaten their long-term survival.

While UEFA’s rules are only applicable to clubs participating in European club competitions, the principles have been adopted across domestic football league competitions in Europe. Their impact has been significant: according to UEFA, net losses in 2009 of €1.6 billion across Europe’s top division clubs were turned into a collective profit of €140 million by 2018, while overdue payables (to other clubs, employees and authorities, including UEFA) have essentially been eliminated. There have also been criticisms, such as the regulations’ impact on the growth and cementing of the gap between large, financially powerful clubs and their smaller rivals; and there have been allegations of flouting of the rules by certain clubs (La Liga has filed a complaint against Paris Saint-Germain and Manchester City for repeated breaches of FFP rules) and questionable sponsorship deals. But overall the decision to introduce regulation on European club finances has generally been well received.

Earlier this year, UEFA announced it would introduce an updated set of regulations under the new name of “Financial Sustainability and Club Licensing Regulations”, citing a new financial reality – in part driven by the Covid-19 impact on operating revenues and player trading profits while wage costs remained largely fixed – which led to unprecedented losses across leagues. The existing FFP regulations were felt to be inflexible and incapable of addressing the ad hoc and myriad challenges posed by the pandemic, prompting UEFA’s review and update.

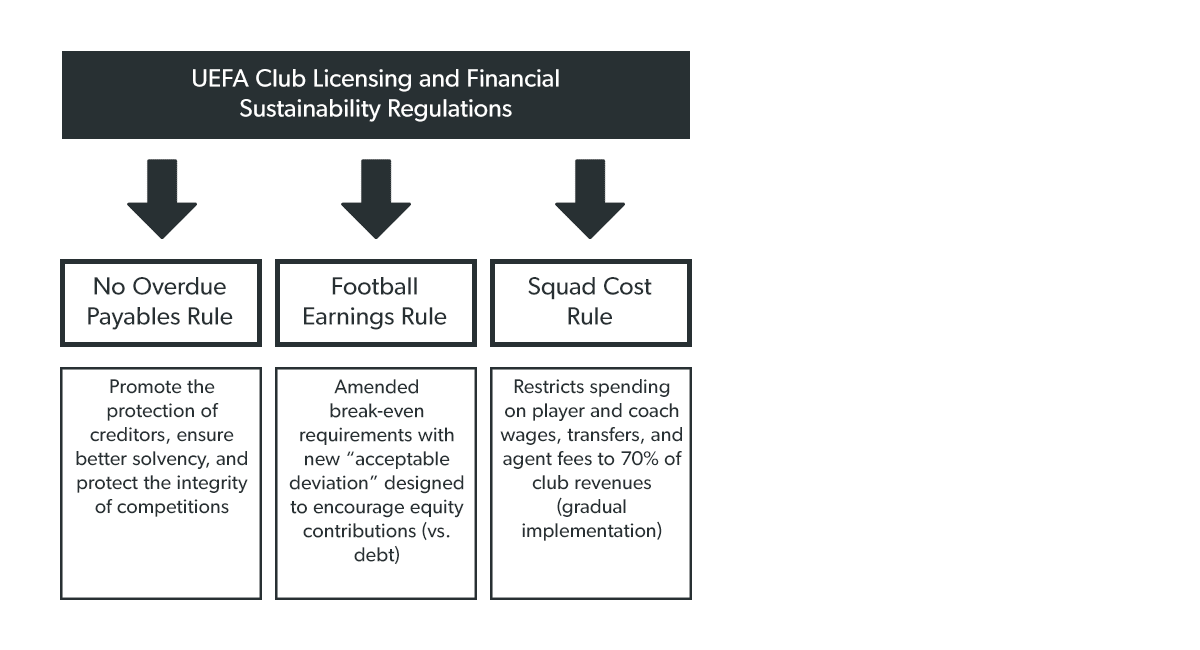

What are the new regulations?

According to UEFA, the first revision to their financial regulations since 2010 “will ensure that all clubs will have to be stable, solvent, and keep their costs under control. The package of new measures includes ways to encourage football clubs to build equity and invest in infrastructure and youth development for their long-term benefit. Stronger balance sheets can provide the first line of defence against revenue shortfalls. Closely aligned to the objective of strengthening balance sheets is the need to make a meaningful move towards better cost control.”

The element of the new package which attracted the most attention, and to which the rest of this article will be devoted, is the Squad Cost Rule, which some have referred to as a “salary cap in all but name”. Many commentators have long argued for the introduction of controls on player wage costs, often pointing to the controls in North American sports leagues which – along with a closed-league system – have played a major role in avoiding the financial perils experienced by sports clubs in Europe and have helped accelerate the value of sports franchises on the other side of the Atlantic. This new rule represents the first attempt to bring the same kind of control to European football.

The Squad Cost Rule

The Squad Control Rule restricts spending on player and coach wages, transfers, and agent fees to 70% of club revenues. As we will see, the immediate implementation of this regulation would present a very significant challenge for a lot of clubs, so it will be implemented gradually with the percentage set at 90% in the 2023/2024 season and 80% in 2024/2025, before moving to 70% in 2025/2026. According to UEFA, the aim is to provides a direct link between income and squad costs, “to encourage more performance-related costs and to limit the market inflation of wages and transfer costs of players”.

The rule applies to all football clubs qualifying for the group stages of the UEFA Champions League, Europa League, or Europa Conference League. It is calculated as the proportion of employee benefit expenses, amortisation/impairment of player (or head coach) registration costs, and agents and intermediaries’ costs (the numerator) over adjusted operating revenue and net profit/loss on disposal of player/head coach registration and other transfer income/expenses (the denominator). Disciplinary measures will be calculated proportionately to the level of excess, with increasing penalties for multiple breaches of the rule.

For example in 2025/26, if a Club earnt £100m from its football-related revenues, it would only be allowed to spend 70% of that amount (i.e. £70m) on its squad.

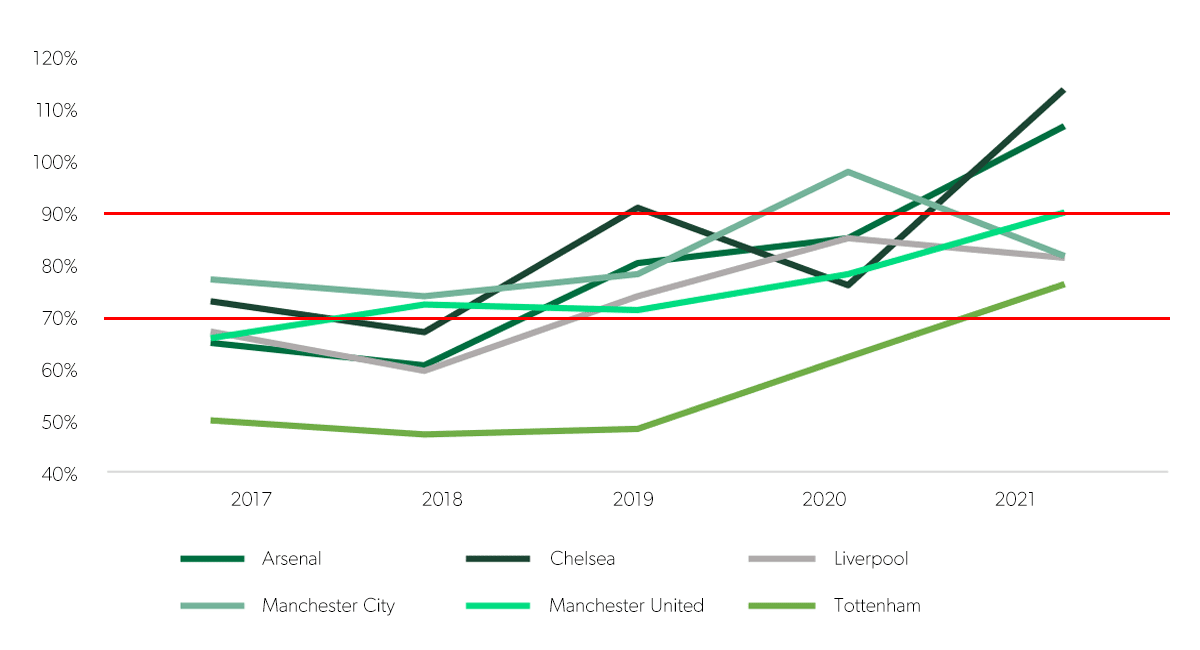

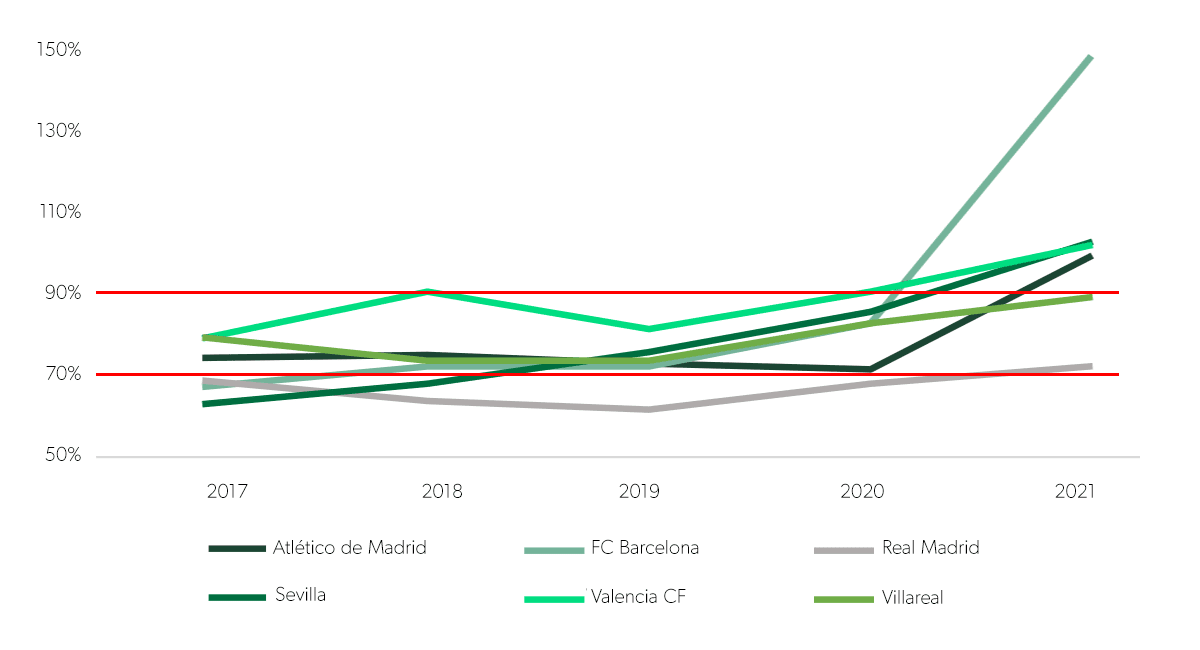

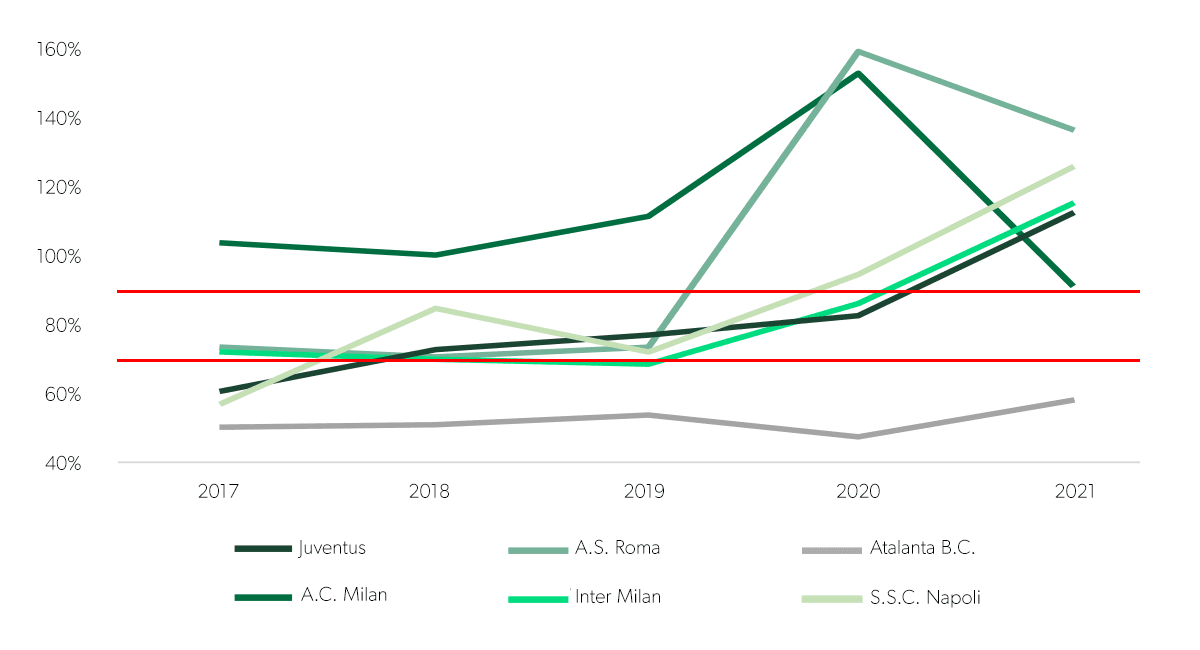

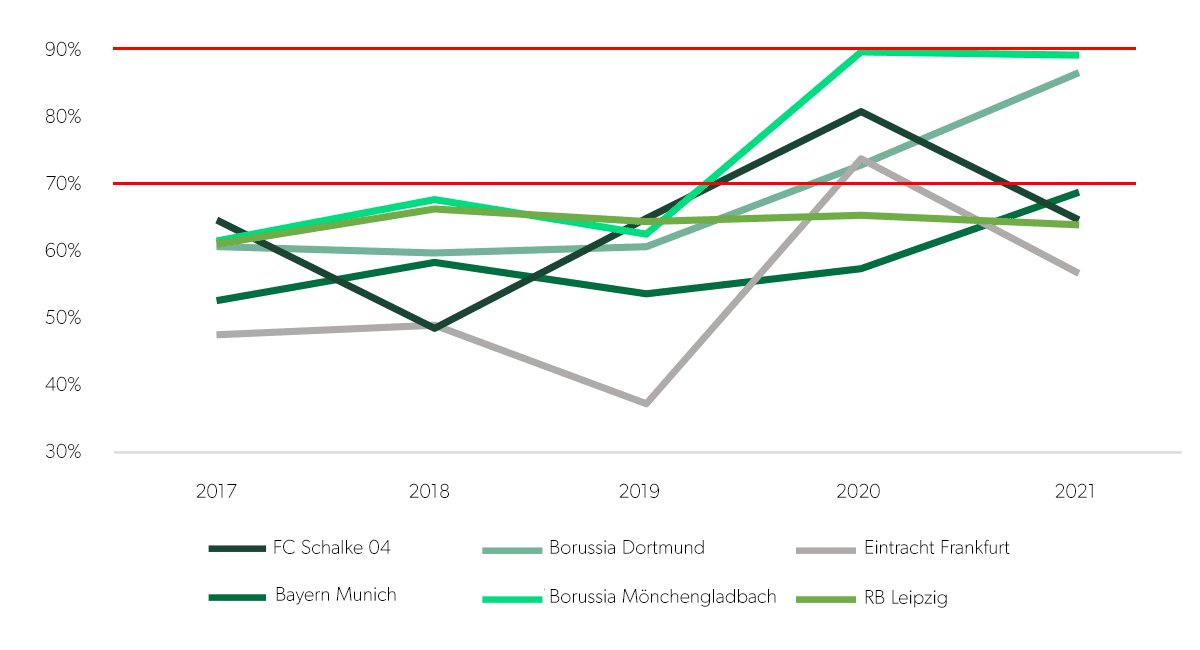

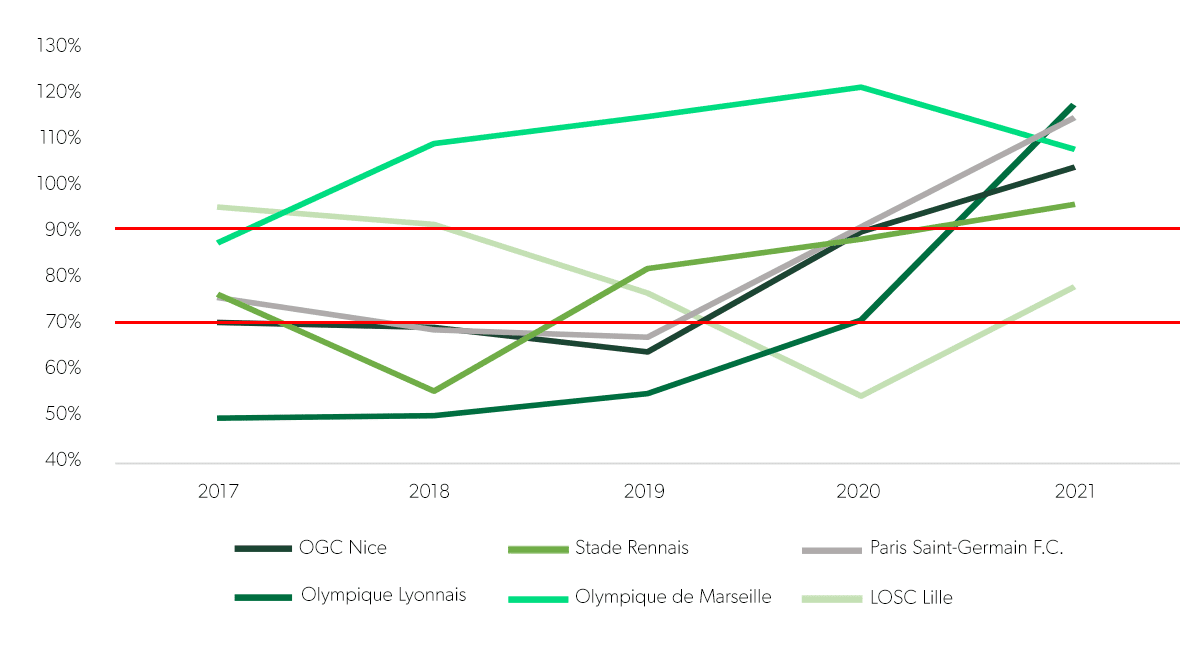

To understand how the rule might look when implemented, the below graphs show what the new squad cost ratios for the six largest clubs by league would look like when applied to the last five seasons.

Note: for simplicity, the ratios shown in the graphs are approximate and not 100% accurate. They are calculated as the sum of total wages (the vast majority of which will be playing staff, but not all) and player amortisation divided by the sum of club turnover, profit on player sales net of player impairment. All measures are for the financial year corresponding to each football season, while UEFA will base its calculation on the calendar year to 31 December except net profit/loss on disposal of player (or head coach) registrations and other transfer income/expenses, which is calculated as the 12-month average of the last three calendar years to 31 December during the licence season. Finally, accounting differs between leagues and even between clubs; data is taken from Off The Pitch.

Premier League

- As in all leagues, the squad cost ratio has been trending upwards through the seasons impacted by Covid-19

- In 2020/21 all but two clubs were below the initial 90% ratio to be imposed; Arsenal and Chelsea surpassed 100%

- Tottenham Hotspur’s ratio was at around 50% until 2018/19, well below the limit, and is only just over 70% in 2020/21

La Liga

- Salary cap controls are already in place in La Liga and the major club ratios are bunched close together

- Barcelona’s dramatic ratio increase in 2020/21 of nearly 150% was driven by a 19% loss in revenues to €590m

- Arch-rivals Real Madrid maintained a ratio under 70% until 2020/21 when it went slightly over to 72.4%

Serie A

- The squad cost ratios surpassed 90% at five of the biggest six clubs in Serie A in 2020/21, and two of those the prior year

- AS Roma’s ratio surged in the last two reporting periods as profit on player sales and revenues both fell sharply

- Atalanta’s dramatic rise in fortunes on the pitch has not been driven by out-of-control spending

Bundesliga

- Average squad cost ratios are the lowest amongst the Big Five, rising from 58% in 2016/17 to 71% in 2020/21

- RB Leipzig has maintained a ratio below 70% while Frankfurt and Schalke only broke this threshold in 2019/20

- Borussia Mönchengladbach’s rise to 90% over the last two reporting periods was driven by negligible player trading profits

Ligue 1

- Average squad cost ratios are the highest amongst the Big Five, rising from 72% in 2016/17 to 107% in 2020/21

- Olympique de Marseille has consistently had a ratio above 90% driven by structurally high wages relative to revenues

- LOSC Lille’s rising revenues and player trading profits allowed it to reduce ratios while increasing wages up to 2019/20

Key outtakes

- The new squad cost regulation will likely be strictly enforced, but it remains to be seen whether there will be a notable impact on wage cost inflation and will satisfy the critics of the current financial controls

- Following the implementation at UEFA level, leagues may choose to adopt similar rules for domestic competition, paving the way to greater financial sustainability in the sport and renewed attractiveness to investors