There has been a fierce rivalry between the English and the French for the best part of a millennium. On the sports field, it continues this weekend with the 22nd clash between the Lions and Les Bleus at the Six Nations.

Going further back to the beginning of the first phase of the Five Nations in 1910, the sides have faced each other 70 further times, making this weekend’s game the 92nd match-up. The record stands at 49 English wins to France’s 35, with seven draws. In the World Rugby men’s rankings, France sits just above England in third place, 0.79 points ahead of England in fourth.

According to legend, rugby was invented in England in 1823, and was introduced to France in 1872 by English merchants and students. The game was enthusiastically adopted across the channel (particularly in the south), to the extent that France was ejected from the Five Nations in 1932 after being accused of professionalism in the French leagues at a time when rugby union was strictly amateur.

The top-tier national club competition in France is the Top 14, predecessors of which have been contested since 1892. Across the channel, meanwhile, England’s governing body, the Rugby Football Union (RFU), long resisted the creation of leagues believing they would undermine the amateur ethos of the game. A national knock-out cup competition was finally launched in 1972, which evolved into the Courage Leagues in 1987 and the Premiership in 2002. Ironically, France was the more reluctant to follow when major national leagues started turning professional in 1995.

Unlike in football where the Premier League and Ligue 1 are 75% and 35% foreign-owned respectively, the countries’ rugby clubs are largely controlled by domestic owners. Only one (8%) of the Premiership’s owning entities is not British-born – Newcastle Falcons owner Semore Kurdi, born in Jordan but now an established businessman in the Tyne valley – while the Top 14 has three foreign-born owners (21%): British-born Simon Gillham at Brive, Syrian Mohed Altrad at Montpellier Hérault and German Hans-Peter Wild at Stade Français.

France well ahead on revenues and profitability, England helped by CVC

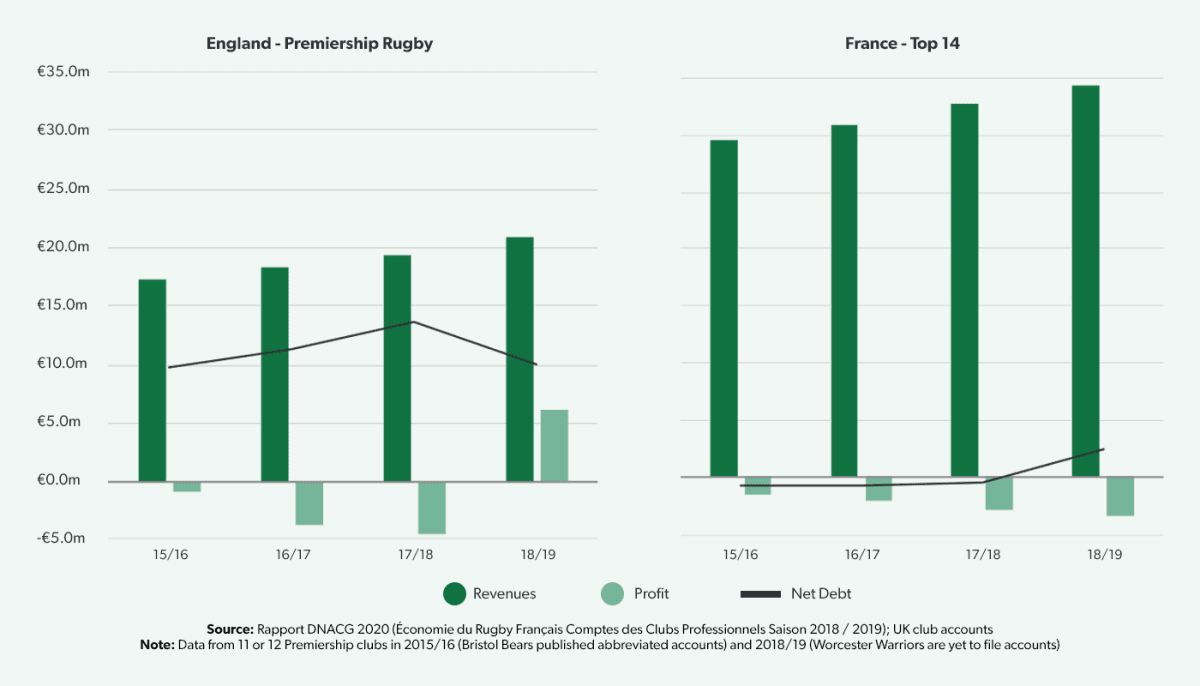

With a longer history of organised league competition, it is perhaps not a surprise that the Top 14 is financially considerably stronger than the Premiership. Average club revenues in France’s top division reached €34m in the 2018/19 season, 64% higher than those in England at €20.9m – although growth is slightly faster in England with a three-year CAGR of 6.3% vs. 5.0% in France, meaning the French revenue advantage has reduced from 70% in 2015/16.

The injection of capital to the English Premiership as a result of CVC’s acquisition of a 27% share of the league reversed the downward trajectory in club profits, as an average loss of €4.6m in 2017/18 went to an average profit of €6.3m in 2018/19, after a rapid decline from a loss of only €0.8m in 2015/16. Every club declared a profit in 2018/19 except Saracens (and Worcester Warriors which is yet to publish its accounts). Net debt levels also fell to €10.3m per club, after rising to €13.5m the previous year.

Losses are increasing in the Top 14, from an average of €(1.5)m per club in 2015/16 to €(3.4)m in 2018/19. Net debt has only reached €2.5m per club in the most recent accounts, prior to which clubs had maintained around €0.5m positive cash reserves – indicating that clubs’ losses have historically been covered by owners.

While Top 14 losses are increasing and net debt was €2.5m per club in 2018/19, clubs have previously held around €500k in positive cash reserves – indicating that losses have historically been covered by owners.

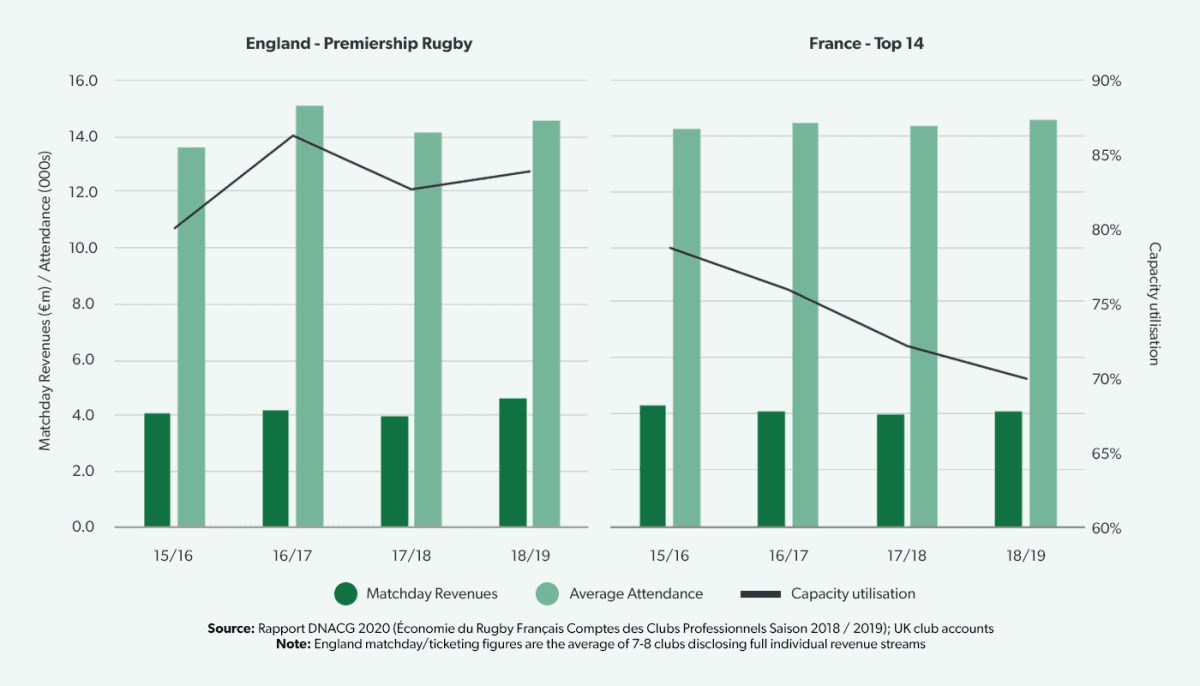

Similar matchday revenues and attendance figures, capacity utilisation falling in France

In the past few seasons, rugby attendances and matchday revenues in England have caught up with those in France. Premiership clubs disclosing matchday income separately in their accounts posted average revenues of €4.6m in 2018/19, up 11% over the three seasons since 2015/16, while average attendance across all clubs was up 7% in the same period to 14,507.

This number remains a fraction (less than 1%) behind the French average attendance of 14,624 – although crowds have climbed only 2% in the same three year period and the Top 14 clubs’ matchday revenues have actually fallen by 6% to €4.1m on average.

Interestingly, capacity utilisation at Top 14 stadia has been steadily decreasing, down from 78.8% in 2015/16 to 70.1% in 2018/19, driven by a 15% increase in available capacity across the stadia, weighted by the number of games played. By contrast, Premiership capacity utilisation has increased from 80.1% to 83.9%.

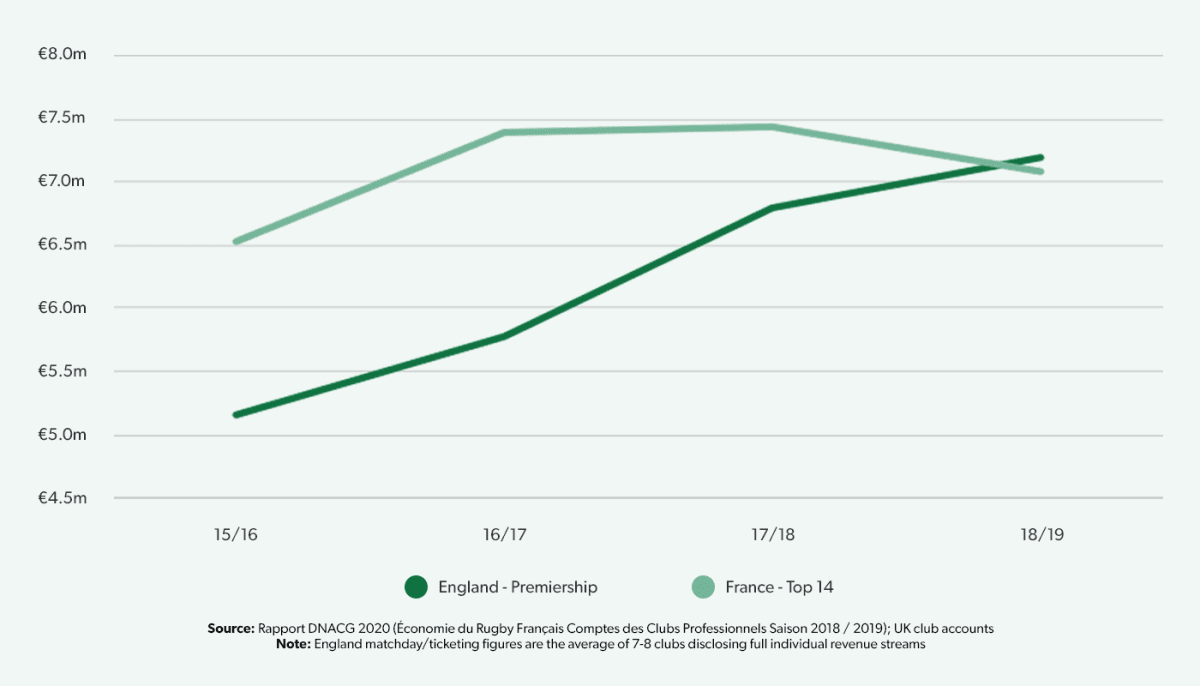

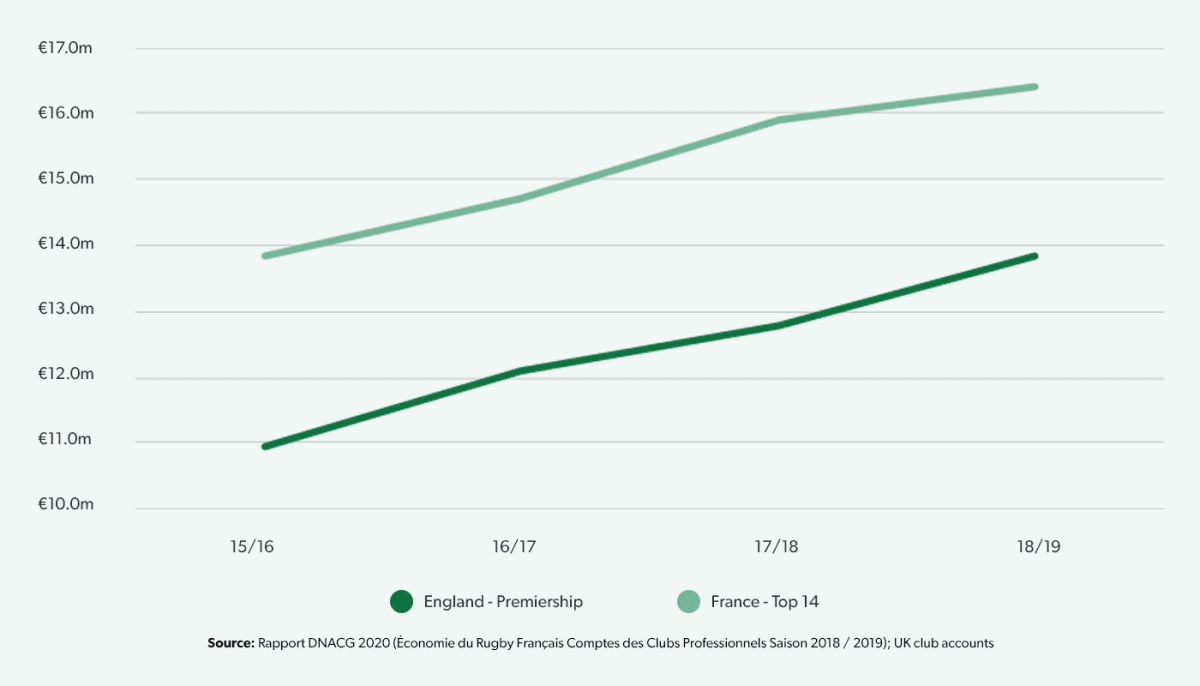

Premiership central distributions have caught up with Top 14

Central revenues – those distributed by governing bodies from broadcasting rights, league commercial revenues and income from national fixtures – are significantly lower in rugby than in football, at 40% of revenues in the Premiership (for those clubs disclosing income streams separately in their accounts) and 21% in the Top 14 – compared to centrally-distributed broadcasting at 56% and 46% of revenues in the Premier League and Ligue 1 respectively.

In the Top 14, central distributions from the Ligue National de Rugby (LNR) jumped 13% in 2016/17, grew slightly in 2017/18 but then fell 5% in 2018/19, to an average of €7.1m per club. There were no changes to the primary broadcasting contract during this period, with annual payments of €71m coming principally from Canal+. By contrast in England, distributions from Premier Rugby Limited (PRL) have been steadily increasing, from €5.2m per club in 2015/16 to €7.2m in 2018/19, overtaking the average paid to French clubs. While the figures are undisclosed, the new contract agreed with BT Sport starting in the 2016/17 season is understood to have offered a significant increase on the previous terms.

The Premiership began a new deal with BT Sport in the 2020/21 season which is reportedly worth £110m per season (€127m at today’s rates). Last week a new four-year deal was signed for the Top 14 to begin in the 2023/24 season, with Canal+ agreeing to pay €114m per season.

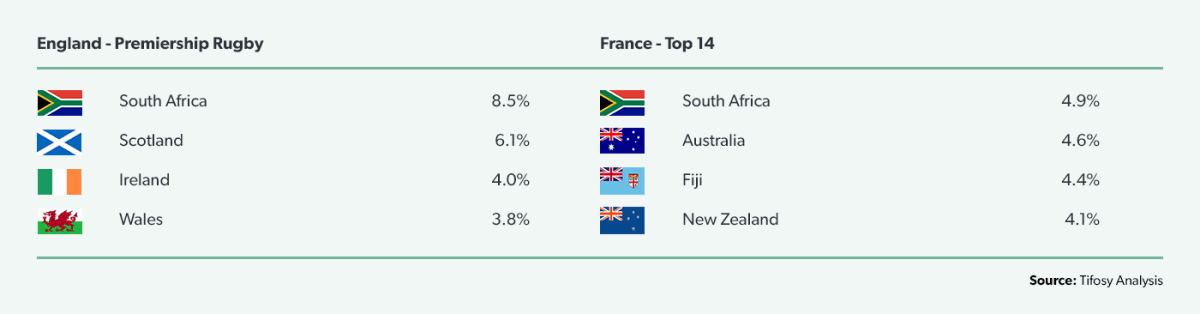

The Premiership has narrowed the wage gap vs. the Top 14 but Covid cuts will reverse the trend

When it comes to the homegrown vs. foreign make-up of their squads, the two leagues are remarkably similar, with 39.7% non-Englishmen in the 527-player Premiership and 36.3% non-Frenchmen in the 586-player Top 14. The most common overseas nationality in both leagues is South African, with the next three most common in the Top 14 all being from Southern hemisphere nations while the Premiership draws more from its neighbour “home nations”. Interestingly, while there are nine English players in the Top 14, not a single Premiership club has a French player on its roster.

Both the Premiership and the Top 14 have cost controls in place with regards to player wages. In England there is a £6.4m / €7.2m salary cap, outside of which two exempted “marquee players” can be paid at each club’s discretion and there are further exemptions for homegrown, elite and injured players. In France, the salary cap stands at €11.3m for the 2020/21 season, with negotiations ongoing regarding the introduction of a marquee player system.

The higher player salaries on offer in the Top 14 have presented a challenge to clubs in England for some time, but the gap has gradually been closing with the average French club’s wage bill of €16.4m in 2018/19 being 19% higher than the average English club’s total salary payments of €13.8m, down from 27% in the 2015/16 season. Indeed, average club wages have increased 8.2% each season in England against 5.8% in France.

However, the gap will very likely widen again in the 2021/22 season. Both leagues will implement temporary reductions to their salary caps to help manage the financial impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. The Premiership’s cap will be cut from £6.4m to £5.0m (€5.6m), a reduction of 22%, while the Top 14 has agreed a less severe 12% drop to €10m. It seems inevitable that French clubs will be planning to make attractive offers to the best players in England to make a move across the Channel during the Summer.

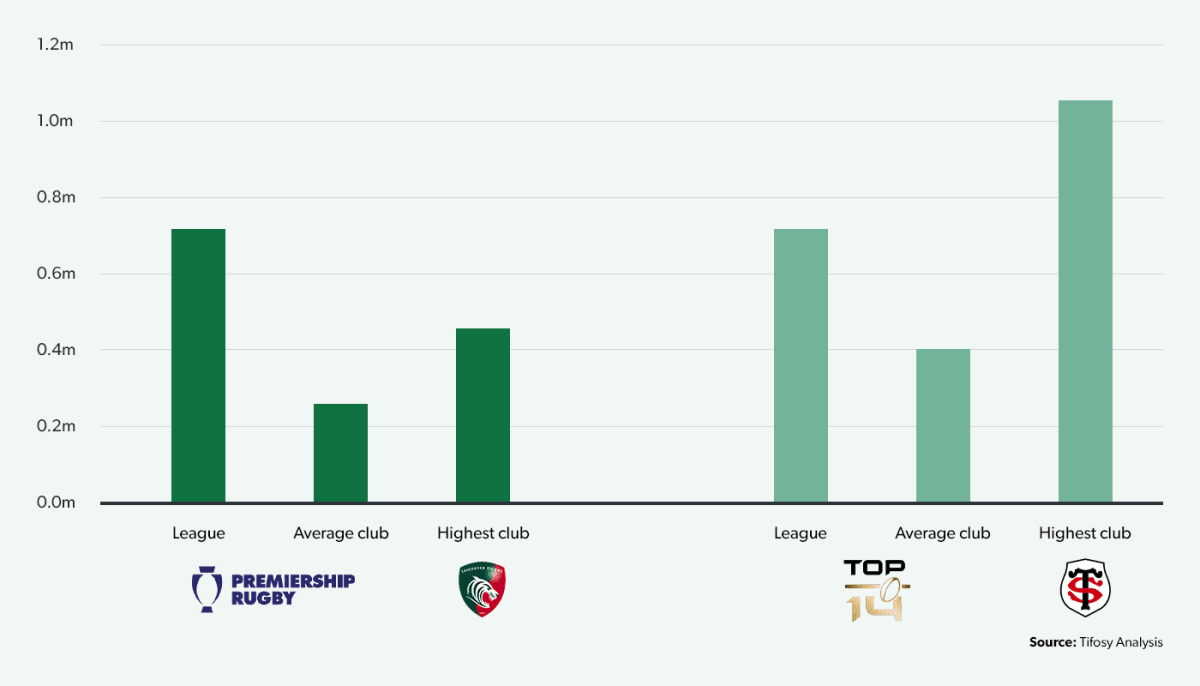

French club rugby is significantly more popular on social media

The earlier establishment of formal league competition in France may also have contributed to the development of strong club fan bases. At the time of publication, social media accounts for the Premiership and Top 14 competitions themselves had very similar reach, with aggregate following of 736k across Facebook, Twitter and Instagram for the French league, just 2% higher than the 718k following the Premiership.

However, the average top-tier club in France has 405k followers across the three platforms, more than 50% more than the 263k for their English counterparts. The most popular rugby club on social media in France (and indeed in the world) is Stade Toulousain with nearly 1.1 million followers, more than double the 464k of Leicester Tigers, the most followed club in England. This may also be reflective of the relative popularity of football in England, where Premier League clubs have an average of 27.6m followers compared to an average of 6.6m followers for Ligue 1 clubs.

Further investment in European rugby

It has already been noted that CVC’s acquisition of a 27% stake in Premiership Rugby had a positive impact on the clubs’ financials. The private equity firm has shown real intent to reshape the global game of rugby, acquiring a stake in the Pro-14 competition (made up of clubs from Ireland, Italy, Scotland, Wales and South Africa) and has held talks with World Rugby, and national governing bodies in New Zealand and South Africa, according to the FT.

In July 2020 news of CVC’s acquisition of 14.5% of Six Nations Limited, the company that manages the Six Nations, was welcomed by clubs and governing bodies fearful of the financial impact of Covid-19. The deal, which reportedly values the competition at just over £2bn, is set to see a further investment of cash into the participating nations, helping to develop both national and club further in both England and France.