The past couple of decades have seen an acceleration of growth in the sports industry, but the growth has not been distributed equally.

The growing importance of access to top tier UEFA competitions and the network effects created by the rapidly accelerating influence of digital media have created a significant and growing gap between Europe’s Big 5 and the many smaller leagues of the region. In North America the MLS continues to grow faster than other sports and both it and the Liga MX of Mexico will no doubt be further invigorated by the World Cup being planned across the three countries in 2026, but there is a yawning chasm between football and the traditional “Big 4” of the NFL, NBA, MLB and NHL.

No wonder then that mergers are being considered between the leagues played in Belgium and the Netherlands, and those played in the US (and Canada) and Mexico. Representatives from Dutch and Belgian clubs – and the countries’ respective FAs – reportedly met in January to discuss the BeNeLiga concept, following the completion last October of an impact report undertaken by Deloitte on behalf of the KVNB. Meanwhile rumours of an MLS/Liga MX merger have been around for some time, and a formal Leagues Cup competition has been played between clubs from the two since 2019. With the US/Canada/Mexico World Cup only five years away, there is momentum in the discussions.

How would these merged leagues work in practice?

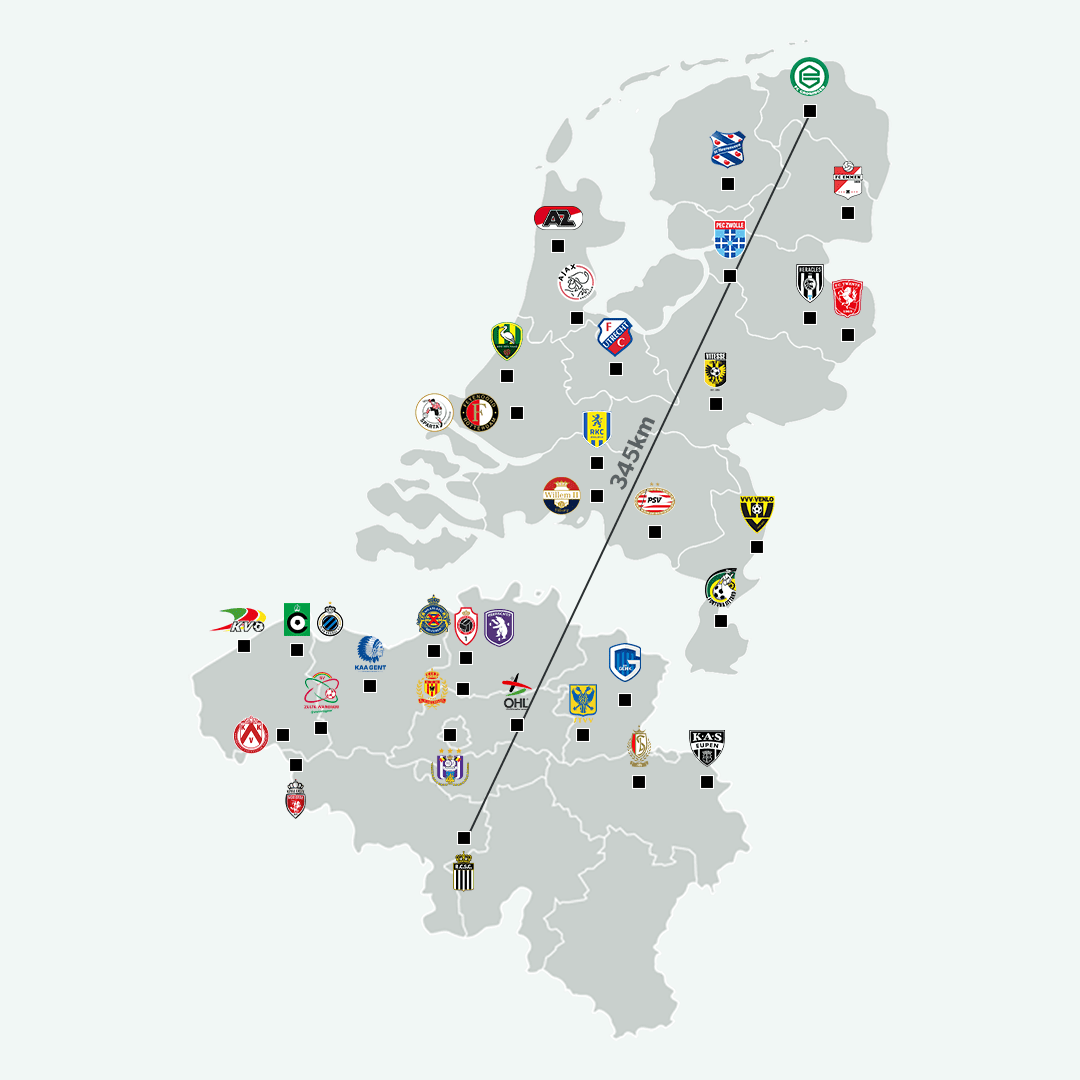

As has been recently reported in the sports media, 25 professional clubs in the top two divisions in Belgium have agreed to explore the formation of a new combined BeNeLiga (a structure already in place in ice hockey) made up of eight teams from the Belgium’s Pro League and 10 clubs from Holland’s Eredivisie with the 2025/26 season pencilled in for its inaugural season. Clubs not making the cut for the top division would play in a restructured national league system in each country – from which promotion would be possible to the BeNeLiga, while each nation’s cup competition would continue to be played as currently. With less than 350km (as the crow flies) between the current most northerly top tier Dutch club (FC Groningen) and most southerly top tier Belgian club (Sporting Charleroi), practicalities of travel would not present a major barrier.

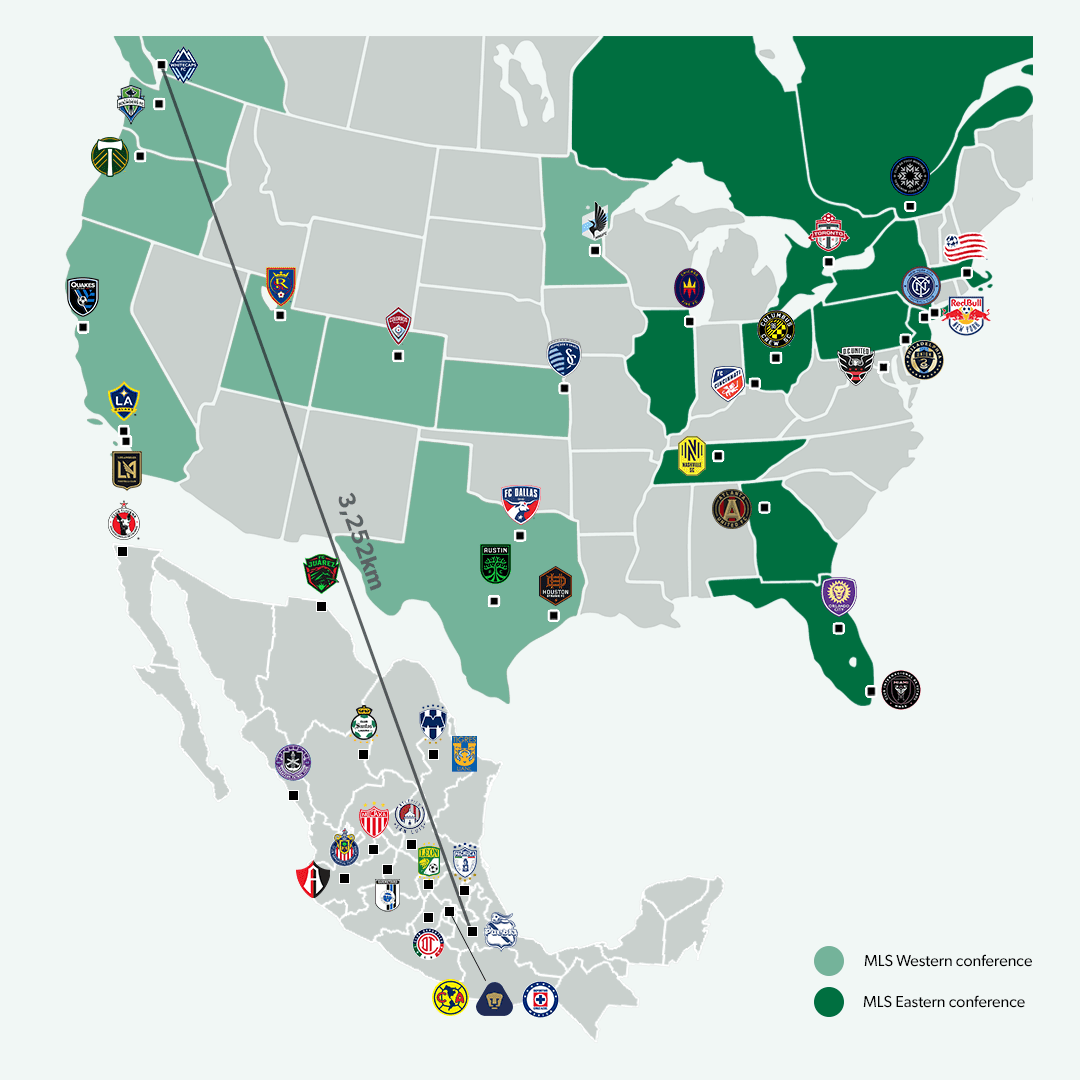

A proposed merger of the top leagues in Mexico and the US/Canada would have bigger challenges to overcome. The MLS is on course to reach 30 clubs by 2022 while Liga MX has 18 – a total of 48 if combined into one league. Practically, the most sensible way to split the clubs would be simply to add a Southern Conference to the existing Eastern and Western Conferences of the MLS. Balancing the numbers at 16 each would be a matter of adding the clubs on the US/Mexico border (Club Tijuana and FC Juárez) into the Western and moving one from the Western to the Eastern (most likely Minnesota United). But this might dissatisfy those looking for regular interaction between American and Mexican sides, who might push for a tiered system – the obvious drawback being the practicalities of travel. Would the sporting directors and players unions of North American clubs accept the increased impact on players of regular long-haul travel when the distance between the most southerly Liga MX club (Club Puebla) and the most northerly in the MLS (the Vancouver Whitecaps) is 3,250km?

Two further considerations are of concern in North America, both concerning key differences between the current management of the two leagues. While the first of these – the fact that the MLS season runs between March and November while Liga MX follows the standard European pattern of August to May – seems like a minor barrier when considering the potential benefits of a merger. The second would likely be more of a challenge, however: in keeping with other American sports the MLS does not have a relegation system while Liga MX clubs are relegated into the Liga de Expansión MX; how happy will supporters of Mexican football to lose drama of relegation, or will US and Canadian club owners be willing to lose the financial stability of a closed league system?

An attempt to close the gap on key league metrics

A major driver of the thinking behind merging leagues is to compete more effectively with larger regional leagues. As Club Brugge president Bart Verhaeghe said in an interview with French newspaper Le Monde, “We are setting up a competition together with the Netherlands to reduce the gap to the five top European countries. Belgian football is waking up and has entered modernity. We could tap into a market of 28 million people.”

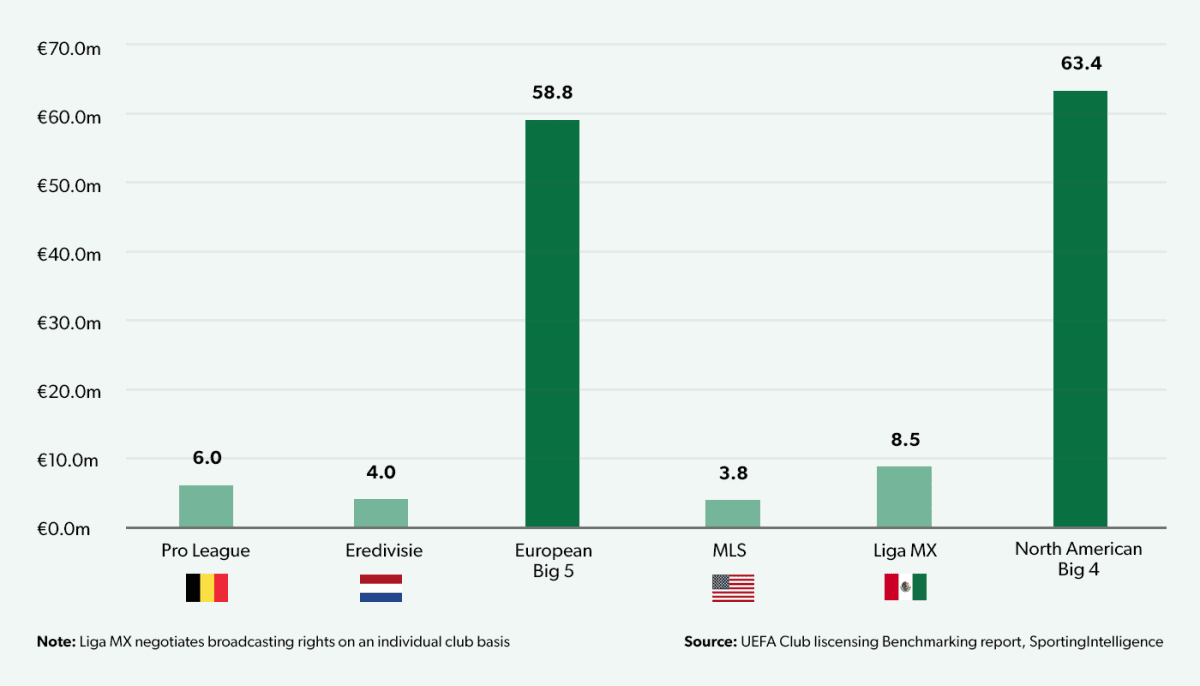

Looking at broadcasting revenues today, the gap is significant. In Belgium and the Netherlands, clubs receive an annual payment of €6.0m and €4.0m respectively, compared with an average of €58.8m for clubs the Big 5 leagues – around 12 times the Belgian-Dutch average. Similarly in North America, MLS clubs receive €3.8m per year and Liga MX clubs €8.5m, compared to an average of €63.4m for clubs in the Big 4 leagues of the NFL, NBA, MLB and NHL – around 10 times the two soccer leagues’ club average.

Last year, a report commissioned by Deloitte estimated that the post-merger BeNeLiga could generate between €250m and €400m a year in television rights – €14m to €22m per club. If the high end of this range could be achieved, clubs in the new division could reach 37% the size of the Big 5 average, a significant improvement on the current situation. Both leagues' existing domestic broadcast deals end in 2025, a key factor in the proposal to launch the combined league in the following season.

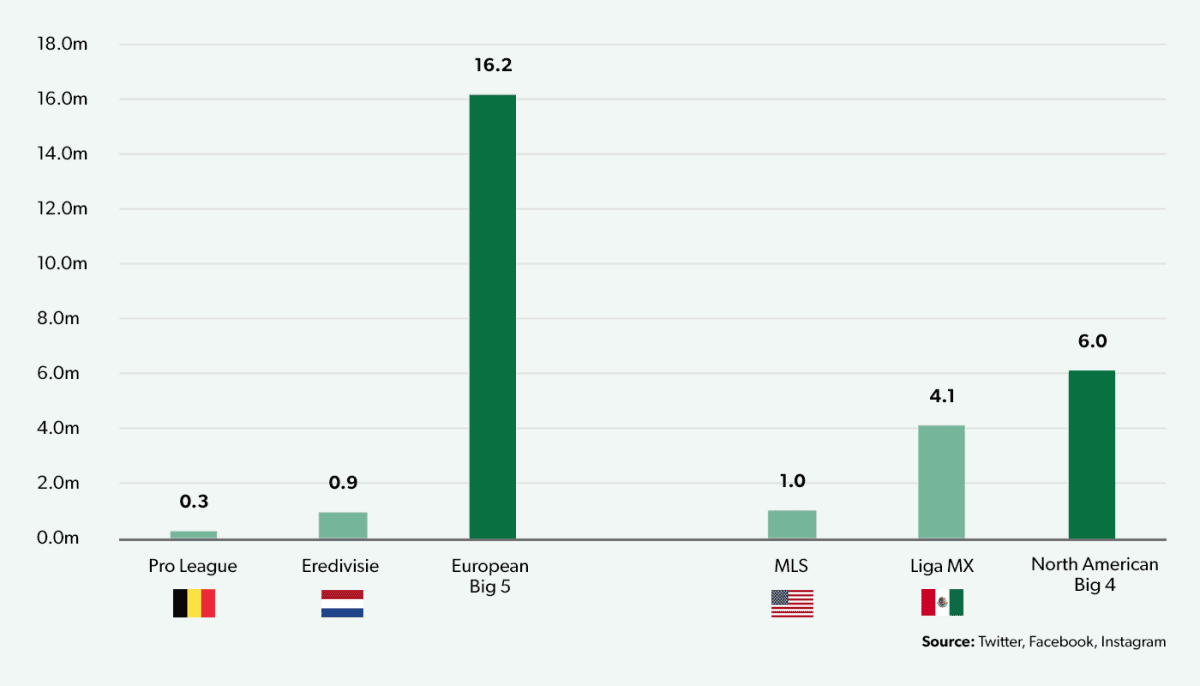

On social media, the gap is significantly larger in Europe. Clubs in the Belgian and Dutch top divisions have an average of 0.3m and 0.9m respectively across Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. The average across these two leagues, 0.6m, is only 4% the following of the average club in the European Big 5. Assuming the merger took the eight most followed Belgian clubs and the 10 most followed Dutch clubs, the average would be 1.1m – an improvement but still only around 7% the average Big 5 club. Architects of the merger will be hoping that pitting the largest clubs of each division against each other will create a platform for higher domestic and international supporter engagement.

Across the Atlantic, clubs in Liga MX already average 4.1m followers across Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, already higher than the averages in Major League Baseball and the NHL and a respectable distance from the Big 4 average of 6.0m. The MLS average is 1.0m, already ahead of the longer-established Pro League and Eredivisie but a long way off the rest of North American sport. One benefit seen in the proposed merger is presumably the acceleration of international engagement for MLS clubs.

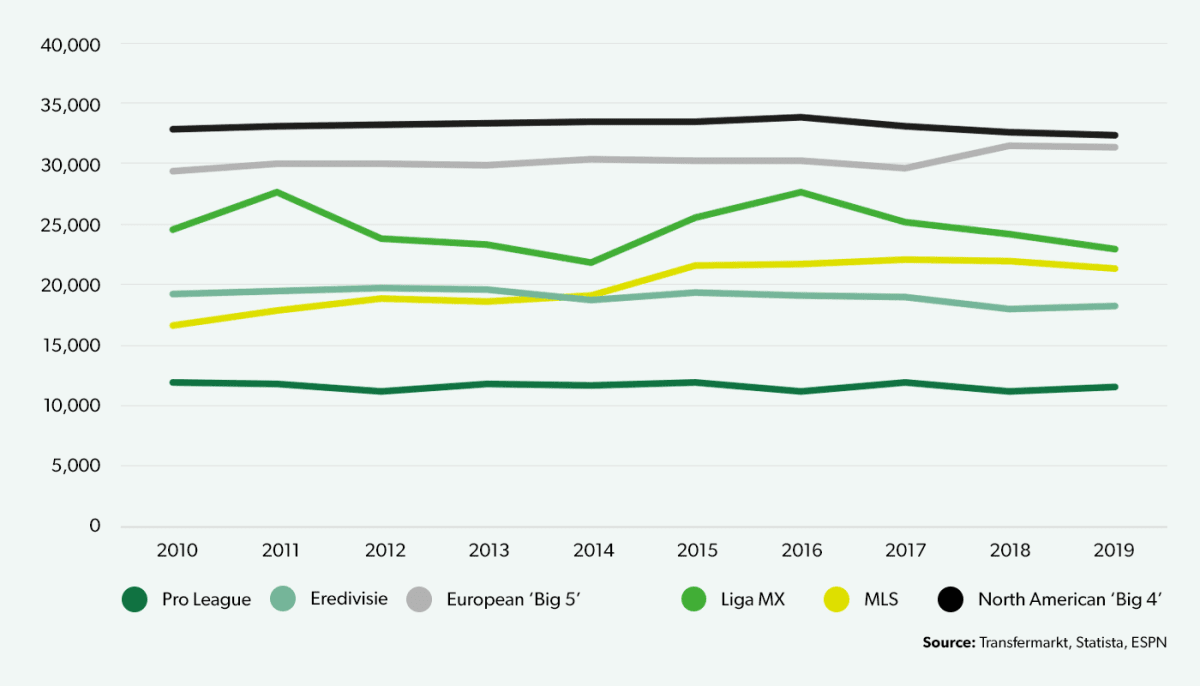

Attendances in the two North American soccer leagues are higher than in Belgium and the Netherlands. The latter two have averaged around 11.5k and 19.0k respectively over the last decade – the Eredivisie experiencing a fall of around 1.5k in the last four years. The Big 5 average of over 30.0k is a factor of city population as well as popularity of the clubs and leagues and structural interventions would need to be made to allow bigger crowd sizes for some clubs.

Meanwhile the MLS has seen growth to reach 21.7k over the last five years while Liga MX has seen peaks of 27.5k and lows of 22.0k over the decade. The major North American sports continue to command higher attendances of nearly 35.0k, although there has been some decline in the past four years; the gap is nevertheless not as large as it is in Europe.

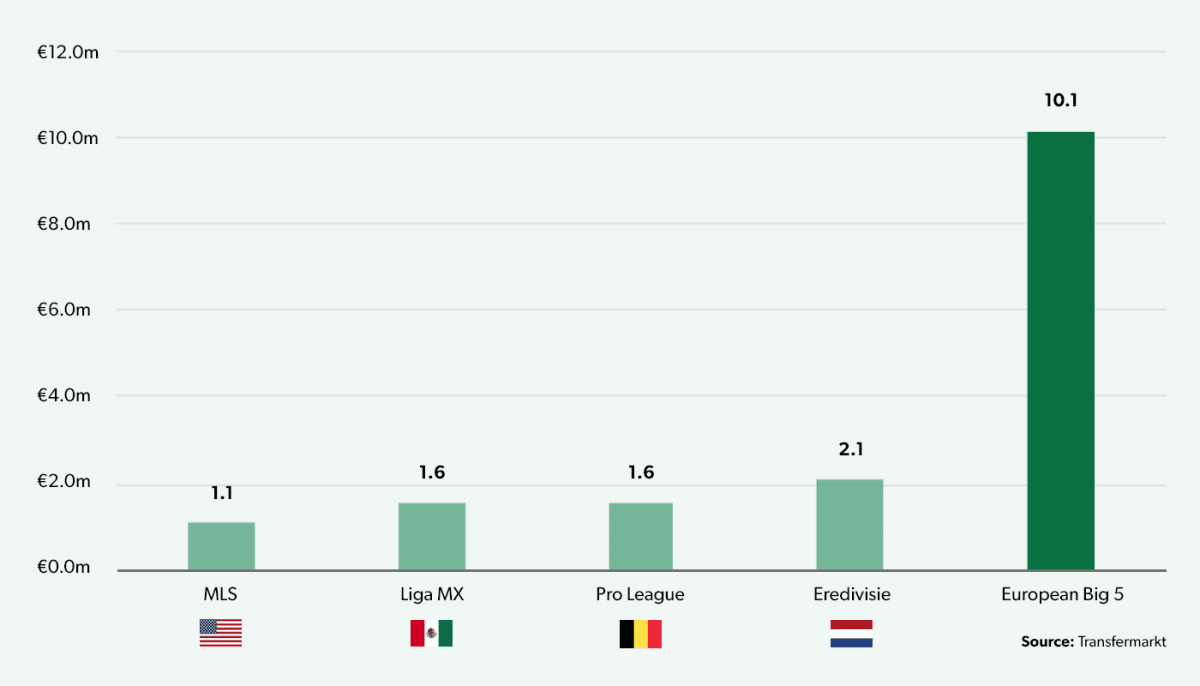

Squad value and transfer expenditures trail the competition

Turning to the primary way in which clubs deploy revenue – buying and paying players – the gaps are substantial. The current squad values between the football leagues are illustrative. Average player value in Belgium and the Netherlands is €1.8m, in the MLS and Liga MX €1.3m. These compare with values of €10.1m on average in the Big 5 leagues, with the lowest being €6.5m on average in France’s Ligue 1 up to an average of €16.6m in the Premier League.

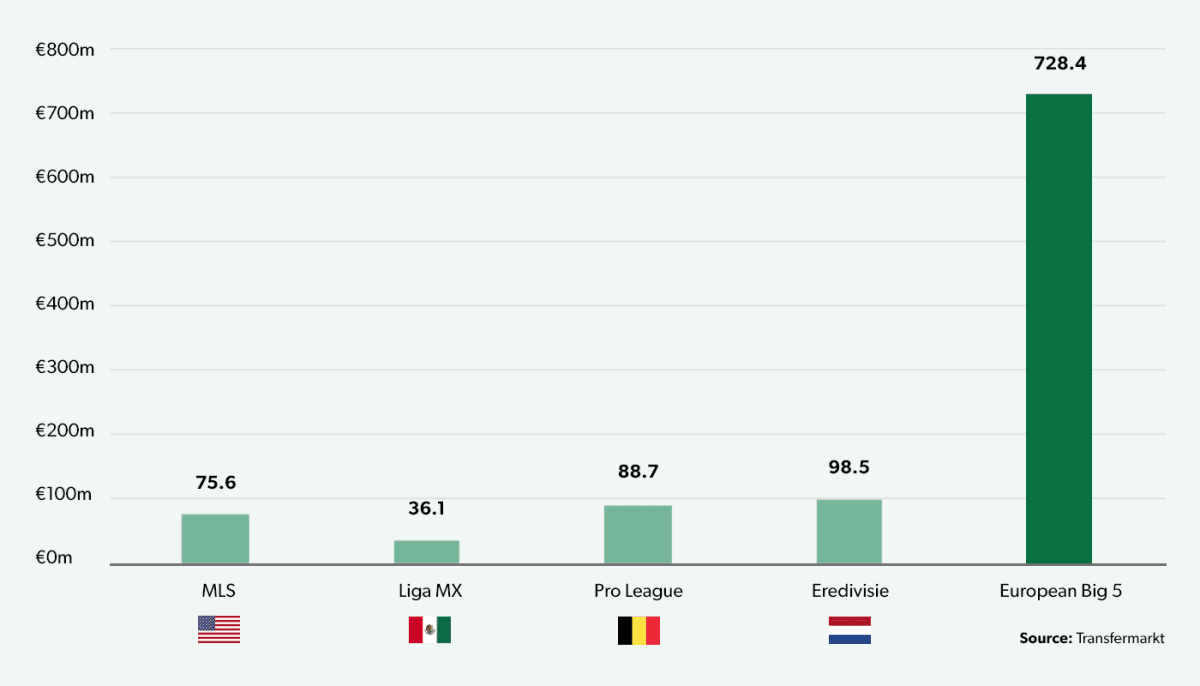

Looking at transfer spending in football – and so excluding the North American “Big 4” for the moment – the leagues proposing to merge are currently significantly off the pace. Player acquisition spending averaged €93.6m for the Pro League and Eredivisie and only €55.9m for the MLS and Liga MX, compared with €728.4m for each of the Big 5 on average.

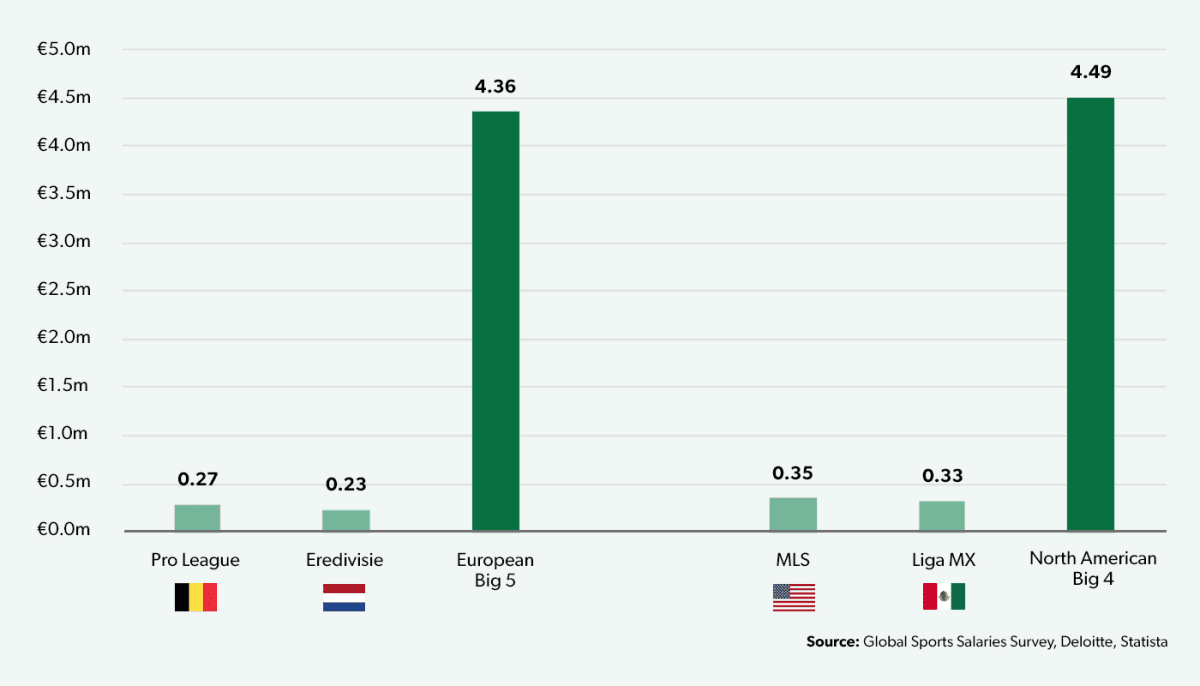

The picture is similar on wages: a top-division player in Belgium or the Netherlands can expect to earn between €230k and €270k, while that number ranges from €3.2m in Ligue 1 to €5.9 in the Premier League – an average of €4.4m across the Big 5. A significant improvement in revenues would enable top clubs to compete more effectively for talent, improving the quality of the product and helping to develop revenues further. Across the Atlantic, the discrepancy between football and other sports is similar, with MLS players receiving €350k and Liga MX players €330k on average. In the USA and Canada the task is two-fold – attracting talent from the European football leagues and also encourage more athletes to play football by closing the gap to the average of €4.5m paid in the “Big 4” – from €3.4m in the NHL to €6.8m in the NBA.