The earliest sports practiced by Chinese people were dragon boat racing and various martial arts, but evidence exists of a game similar to football named Cuju being played as early as 50 BC.

However, the development and expansion of a modern sports industry in China began relatively recently, coinciding with economic reforms led by Deng Xiaoping which saw the Chinese Communist Party adopt a "socialist market economy”. According to a 2015 paper published by Jie Zhang of Jinan University in Shenzen, “China's sports have been gradually transformed from a type of public welfare under the planned economy to a business under the market-oriented economy since the implementation of the reform and opening-up policy in 1978”.

The study notes that China's sports industry has gone through three phases: an exploratory phase from 1978 to 1992 during which China first entered the Olympic Games in 1984 and quickly established a regular place in the top four of the medal table; a formative stage from 1993 to 1996 when professional leagues were setup in football, basketball, table tennis and volleyball; and the development stage since 1997. A 2019 Deloitte report notes that following President Xi Jingping’s election, a paper was published by the State Council in 2014 which “[set] in motion [a] plan to mobilise [the] population and create the world’s largest sporting industry by 2025”.

Professional football is still a relatively new development in China

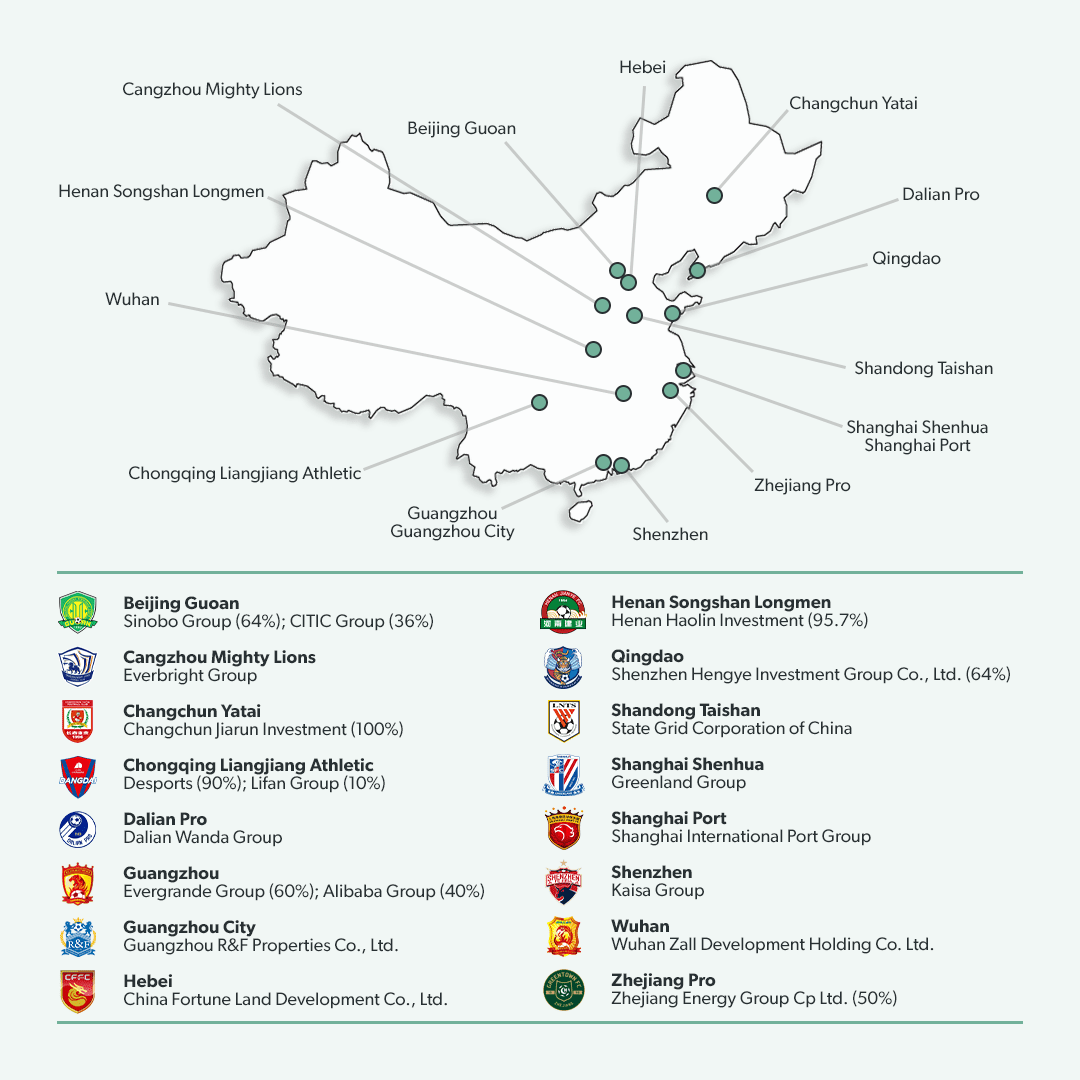

While the modern Chinese Football Association was founded in January 1955 and amateur competitions were played throughout the latter half of the 20th century, the first professional football league, the "Jia A" (jia translates as “first” or “best”) was not established until 1994, after which professional set-ups followed for basketball, table tennis and volleyball over the subsequent two years. The Jia A was reformed as the Chinese Super League (CSL) in 2004 – initially with 12 clubs but rising to 16 by 2008, at the top of four-tier national pyramid comprising a total of 74 clubs. Over the four years from 2015 to 2019, the CSL jumped from seventh to first place in the Asian Football Confederation’s ranking of the region’s club competitions driven by consistent success of its member clubs. The 2021 members are shown below.

As noted in an earlier post, Chinese investors bought heavily into European football in the latter part of last decade, seemingly adopting a strategy of learning from the experts to help build their own football capability and talent. The strategy appears to have changed, more recently, with positions being given up or sold at numerous clubs in Italy, England, Spain and France. In the Chinese Super League, club ownership is 100% local, and until recently clubs could be named after their majority investors, a situation which encouraged owners to invest substantially. However, in December 2020 the Chinese FA announced that sponsors must be removed from club names, forcing all CSL clubs but Shanghai Shenhua to rebrand – with potential consequences on investment into the clubs. This rule was accompanied by the implementation of spending caps, presumably in an effort to bring costs down in line with sponsorship income.

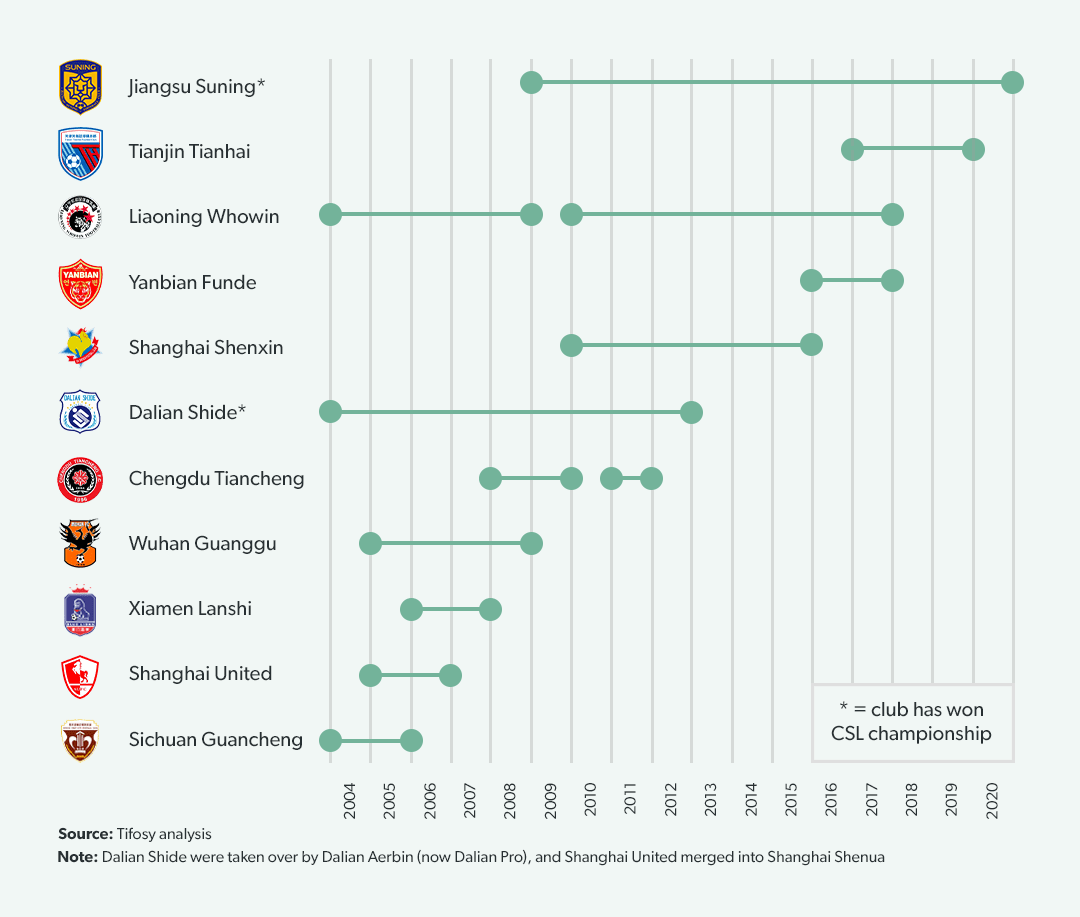

A league dogged by a lack of membership stability

The most successful club of the CSL era is Guangzhou FC, which has won the title a record eight times – all but two of the years since its most recent promotion to the division in 2011 (and finishing runner-up in those two seasons) – as well as delivering a domestic treble in 2012 and 2016 and winning the AFC Champions League in 2013 and 2015. The club’s nearest challenger is Shandong Taishan FC with three CSL titles including a league and cup double in 2006, and one title in the old Jia A.

Aside from winning prizes, the main challenge for members of the Chinese Super League seems to be financial sustainability, with a third of the 32 clubs ever to have played in the division no longer in existence and Tianjin Tigers at high risk of folding. The football world was shocked when it was announced at the end of February that current champions Jiangsu FC would cease operations with immediate effect due to financial issues caused by Covid-19 only three months after lifting the CSL trophy. But Jiangsu is just one of nine clubs to have completely ceased operations in the 17 years since the league’s inception, on top of which a further two clubs have been taken over by or merged into other clubs, and the future of Tianjin Tigers remains in the balance after its parent company – State-owned conglomerate Tianjin Teda – withdrew funding and the club failed to produce the necessary paperwork for the 2021 season before the deadline. It also reportedly owes its players 10 months of salary payments.

The football world was shocked when it was announced at the end of February that current champions Jiangsu FC would cease operations with immediate effect due to financial issues caused by Covid-19 only three months after lifting the CSL trophy.

Perhaps the most spectacular demise was that of Wuhan Guanggu. After the club’s centre back Li Weifeng scuffled with an opposition player during a match against Beijing Guoan, the Chinese FA fined the players and banned them for eight matches. When Wuhan chairman Shen Liefeng refused to accept the punishment and an agreement with the Chinese FA could not be reached, the club withdrew from the CSL. The CFA responded by imposing a further fine, awarding 3–0 wins against them for all their matches in the 2008 season, and banning the club from entering any league competition in the future.

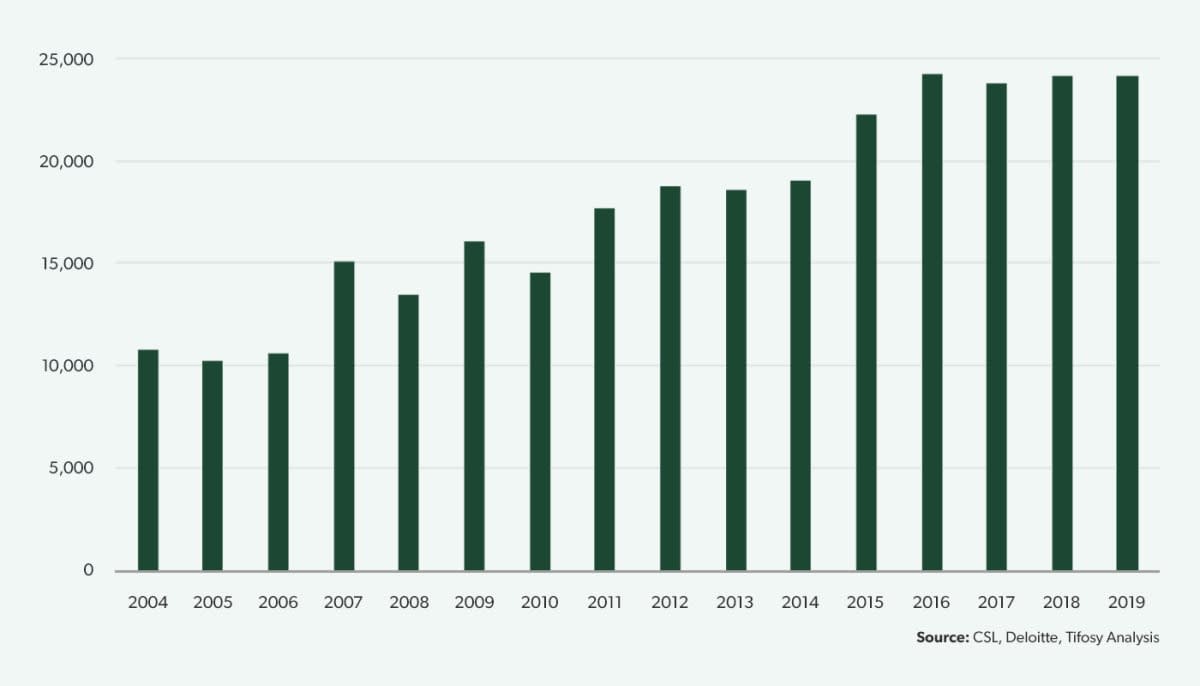

CSL attendances challenging the biggest football leagues in the world

League attendances experienced rapid growth in the 10-year period between 2006 and 2016, more than doubling from around 10k to peak at 24,159 in 2016 before levelling off. Average 2019 CSL attendance placed it fifth-highest amongst global professional football leagues, ahead of the top divisions of Japan, the USA, Mexico and Brazil as well as France’s Ligue 1, but behind the rest of the Big 5. Capacity utilisation rate was 64.0% in 2019, ahead of Serie A’s 62.3% but well behind the 96.1% and 91.4% of the Premier League and Bundeliga respectively, in part due to the relatively larger stadia build for Chinese clubs.

Room for development in broadcasting, league sponsorship higher than Europe

Collective broadcasting rights tendering began from the 2016 season, with an equitable distribution system in place: 10% of funding is reserved for the CFA and CSL, after which 81% is divided equally between the clubs and only 9% is awarded based on final league position.

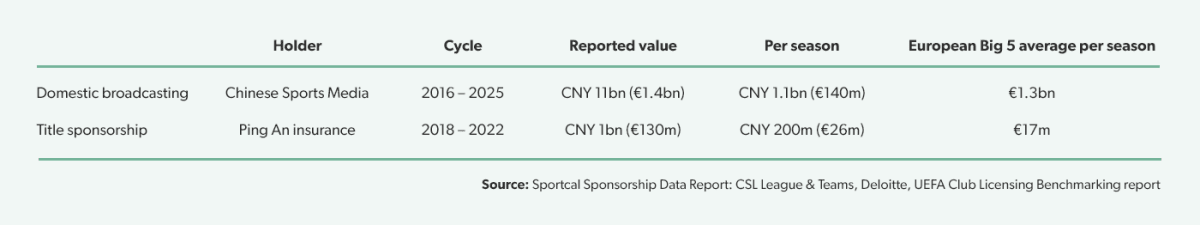

The current media rights holder of the CSL is China Sports Media (CSM) which initially bought the rights for five seasons between 2016 and 2020 and subsequently agreed to extend the original contract to 10 years, up to 2025. The initial price for five years was CNY 8bn (ca. €1bn), increased by only CNY 3bn (€375m) to a total of CNY 11bn (ca. €1.4bn) for the full extended period. This corresponds to a payment of around €140m per season, compared with a current average of ca. €1.3bn per season for the most premium football competitions in the world, the Big 5 in Europe. Internationally, the CSL is broadcast in 96 countries across the world under an agreement between CSM and IMG.

The CSL’s title sponsor is Ping An, a Chinese insurance company. After a four-year initial contract worth a reported CNY 600m (ca. €75m) ran from 2014 to 2017, the company renewed for a further five years up to 2022 in a deal paying CNY 1bn (ca. €125m), amounting to ca. €25m per season – higher than the average of €17m per season currently paid on average by the title sponsors of Serie A, La Liga and Ligue 1 in Europe (neither the Premier League nor the Bundesliga currently has a title sponsor).

Clubs’ individual sponsorship deals have typically been more lucrative, with 2019 revenues of current CSL members ranging from €10.9m at Wuhan FC to €34.9m at Guangzhou FC. The bulk of sponsorship money derives from the title sponsor, which as noted above may be reduced following the changes to club branding rules.

Player development: Chinese FA intervenes to stay on CCP mission

In 2011, President Xi Jinping – an ardent football fan – unveiled his grand scheme to turn China into a footballing super power. He wants his country to host World Cups, and one day to lift the trophy. To date, the national squad has fallen somewhat short of demonstrating progress against this goal. The country has only qualified for the FIFA World Cup once (in 11 attempts, the first in 1958 and then every year since 1982), being knocked out at the Group Stage of the 2002 finals in Japan & South Korea after conceding nine goals against Brazil, Costa Rica and Turkey without reply.

With the strategy of connecting with successful footballing nations in Europe to import skills seemingly no longer in favour, the Chinese Community Party (CCP) is focusing on building capability from within, and has made significant investments at grassroots level. The Chinese FA’s plan includes having 100 million children under the age of six being coached daily at school and 50,000 specialist soccer schools being set up before 2025. There is optimism that the programme will start to bear fruit – in the form of talent – by the end of the decade, by which time China is also expected to have made its first bid for the right to host a World Cup.

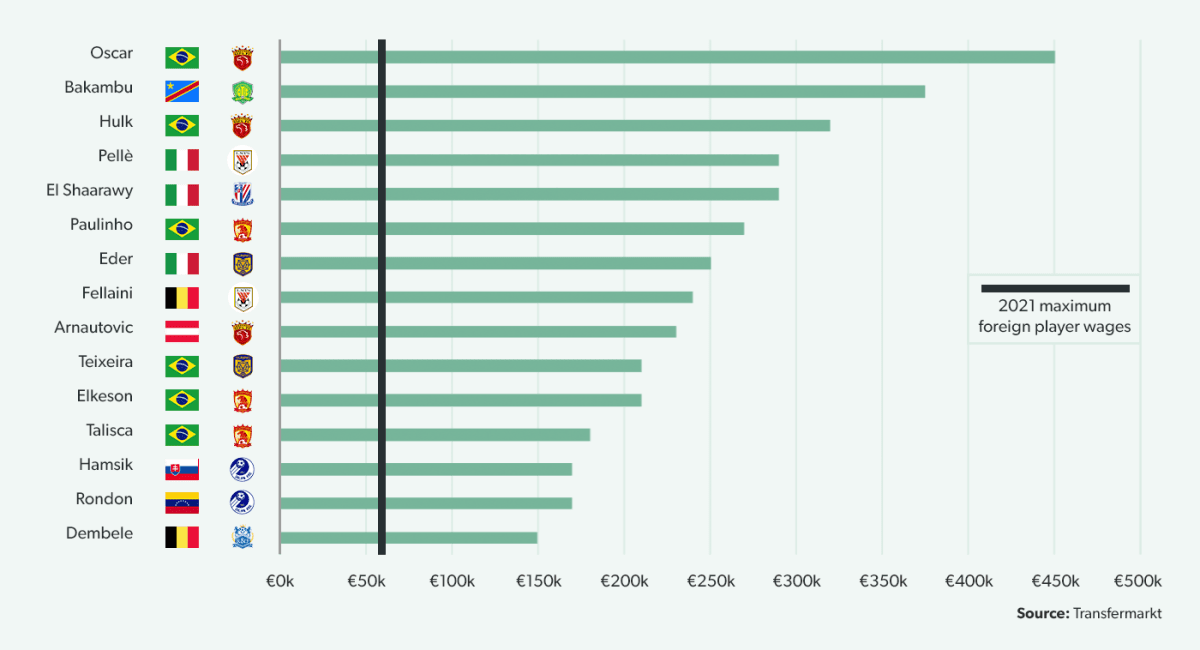

The CSL is also expected to play its part, with measures introduced to help steer a course to national success. New rules were announced ahead of the 2017 season stipulating that Chinese players must make up 27 players of the maximum 31-man squad, with only three foreign players per club being allowed on the pitch during a game. A 100% tax on large transfers was also introduced, with the money raised sent to youth development programs. In December 2020, a salary cap of €3m per year for foreign players was introduced for the 2021 season, well below the levels being paid to stars such as Hulk and Oscar. The maximum salary for Chinese players is CNY 5m (ca. €650k) and total wage bills cannot exceed CNY 600m (€77m), of which less than 15% can be spent on foreign player salaries.

The changes have naturally also had an impact on transfers, as the bigger stars find playing in China less appealing on the reduced salary levels. Prior to the new measures being introduced, foreign stars were arriving in the CSL for up to €60m – the fee paid by Shanghai SIPG to Chelsea for Oscar in December 2016. Other stars such as Hulk and Alex Teixeira commanded similar fees. More recently, however, the number of foreign stars arriving has dropped dramatically – from more than 70 in the European 2017/18 season to just 16 in 2020/21.

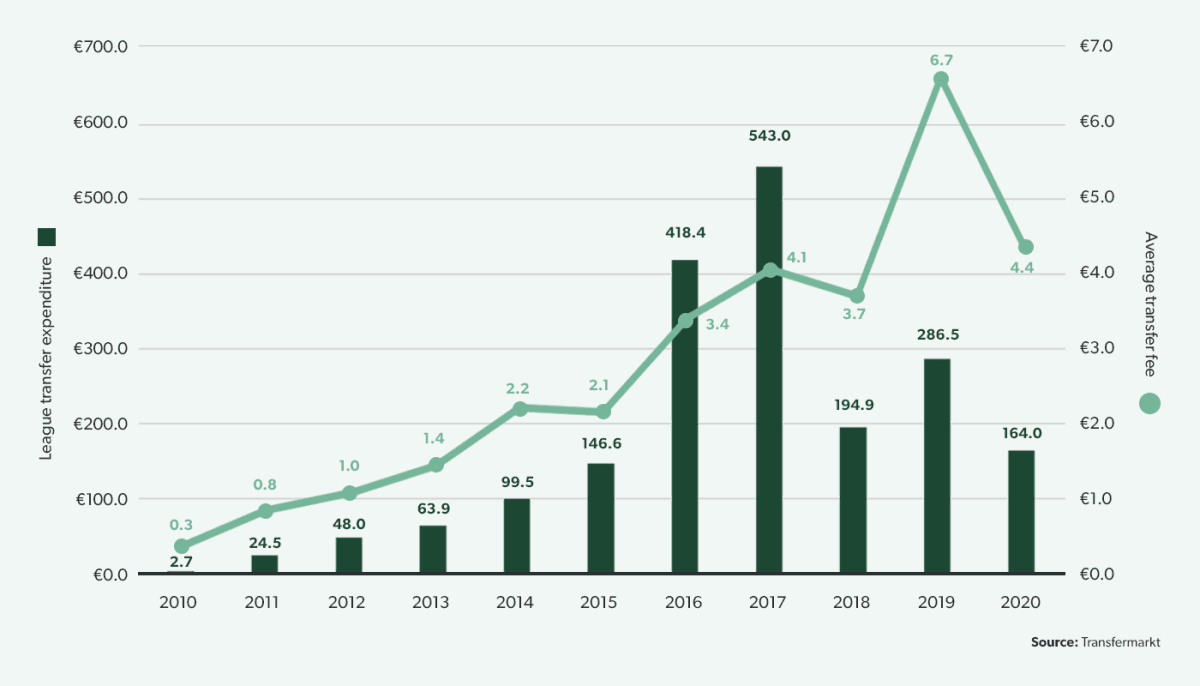

The impact of the changes in approach on transfer expenditure has been dramatic. Clubs in the CSL spent €543m in the peak year of 2017, up from only €2.7m only seven years previously, before cutting expenditure to only €164m in 2020, the lowest level since 2015 and no doubt impacted to some extent by Covid-19. As the number of transfers – especially those involving players from more developed footballing nations – declined in recent years, those blockbuster signings still arriving led to a peak in average transfer fee of €6.7m in 2019, but the average fee fell to €4.4m in 2020.