First recorded in England in 1598, cricket is one of the oldest sports in the world.

It was played for more than two centuries before being seeded aboard by the sailors of the British navy and merchants in trading ships, with evidence for its existence showing up in India in 1721, Australia in 1803, the West Indies in 1806 and South Africa in 1808. Domestic competitions began in the late 19th century, with the first official county championship played in England in 1890 (though unofficially county cricket had been played since early the previous century), with an equivalent already underway in South Africa since the previous year and Australia’s competition starting in 1892.

Shortening the game

Few sports can rightfully claim their matches last longer than those of ‘test’ cricket, the traditional form of cricket, which is typically played over three to five days of at least six hours. In 1951, the concept of limiting the number of overs (each of six balls to be bowled to the opposition batsman) to 50 originated in Kerala, India, allowing a match to be played in a single day. A similar one-day format, this time with 65 overs, was played for the first time in England in the regional Midlands Knock-Out Cup in 1962. One-day cricket grew in popularity over the 1960s and international versions started in the early 1970s.

In response to falling attendance numbers and declining interest in cricket during the late 1990s (the launch of football’s Premier League in 1992 no doubt playing a role), the England and Wales Cricket Board (“ECB”), the governing body of cricket in England proposed Twenty20 (T20) cricket, which would be even shorter than typical One-Day matches. Twenty20 games, with 20 overs would be allotted to each side, would be played over roughly three hours. The inaugural domestic T20 competition (now known as the T20 Blast, or Vitality Blast for sponsorship reasons) was contested in 2003 with teams affiliated to the existing county cricket clubs, who called on their existing roster of players.

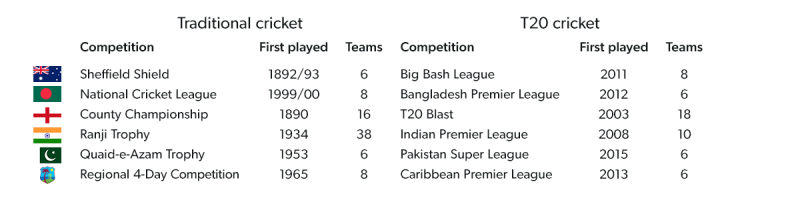

Following the introduction of T20 to international cricket in 2005 and the first T20 World Cup tournament in 2007, the floodgates opened. The Indian Premier League (IPL) launched in 2008 and was the first T20 league to feature prominent international players from different countries. Three years later came Australia’s Big Bash League, followed by equivalents in Bangladesh, the West Indies (Caribbean Premier League) and Pakistan. South Africa's Mzansi Super League was recently scrapped after a failure to secure a 3-year broadcasting contract but Cricket South Africa has recently sold six franchises for a new competition, all to owners of IPL teams

T20 competitions have been established in major cricket nations

Overview of cricket traditional and T20 cricket competitions in major cricket countries

Source: Public information

The Indian Premier League – an inexorable rise?

The IPL was founded in 2007 by the Board of Control for Cricket in India (“BCCI”), with eight founding franchises put up for auction. The league structure was similar to that of USA leagues: a single division, no relegation risk, and wage and spending caps designed to maximize competitiveness. There was also a player draft which saw teams bid for top players from across the world to play for their teams. The tournament format is split into a group stage, during which each team plays the others twice, and a play-off stage, in which the four highest ranking league teams progress, with the winner of the play-off being crowned the IPL champion. The tournament is played over a short two-month window, typically between March and May.

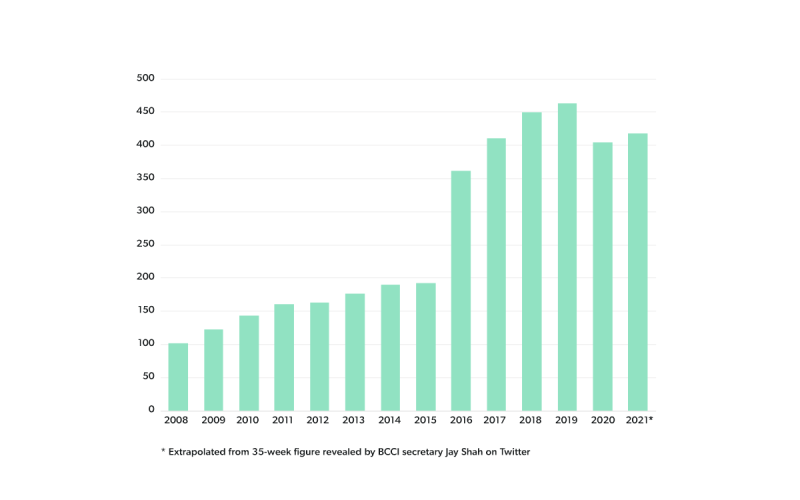

Over the years, the IPL has developed into the biggest cricket product in the world from a viewership and commercial perspective. The number of unique viewers in India grew steadily over the first twelve seasons, peaking in 2019 at 463 million (note, the jump in 2016 is due to a change in the measurement methodology, from the initial provider TAM Media Research, which focused on India’s urban centres, to BARC India, which also covers rural communities). In 2020, when the tournament was hosted in the United Arab Emirates due to the challenges posed by the Covid-19 pandemic in India, a fall in TV viewers of 12.5% was reported, although this has been attributed to cannibalisation from OTT platforms and a partial recovery was seen in 2021. Numbers for the 2022 tournament have not been released.

IPL viewership grew steadily until 2019

IPL unique viewer numbers in India (TAM Media Research 2008-15, BARC India 2016-2021)

Source: Statista, media reports

The league’s success primarily derives from the availability of a very large and enthusiastic domestic market, with a TV audience of 836 million in 2020 (according to India’s Economic Times). Perhaps more importantly, despite cricket’s status as the most popular sport in India, the country lacked a commercially and broadcast-successful domestic cricket league before the arrival of the IPL: the primary focus of the BCCI (Board of Control for Cricket in India) was on the country’s performance in international matches and tournaments, leaving a gap which did not exist to the same extent in other major cricket markets.

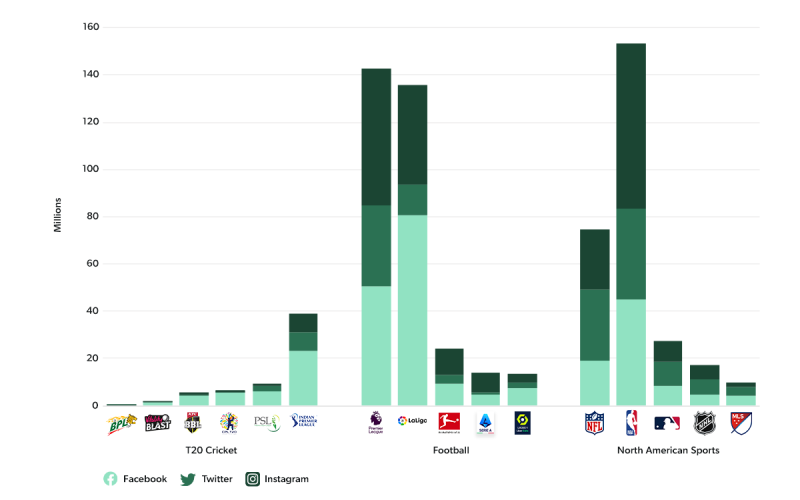

Indeed, the extent to which each governing body has embraced and promoted T20 as a unique entity is visible in the development of social media following for these new leagues. Looking at the aggregate number of followers across Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, we can see that England’s T20 Blast, where the T20 teams form part of the existing county cricket team structure and the league is seen as an add-on to the “main event” of county cricket, has grown a far smaller following than the IPL and its equivalents in Pakistan and the West Indies (Caribbean Premier League) where the leagues have been launched with standalone teams. Australia sits in the middle, maintaining a focus on domestic four-day cricket with its territory-based clubs while setting up the T20 Big Bash League with new city-based teams.

Indeed, as the graph shows, the following of the IPL brand on social media is now larger than all but the top two leagues in Europe and the top two leagues in the US, after only 15 seasons and still largely driven by a domestic audience.

IPL social media following is already ahead of established leagues in Europe and North America

Major T20 competition social media following

Source: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

With the dramatic increase in the value of broadcasting rights for the IPL, there has been a similarly impressive rise in team values. Fees agreed in 2021 for two expansion franchises were 9.5x the original 2008 franchise auction average.

Broadcasting rights growth

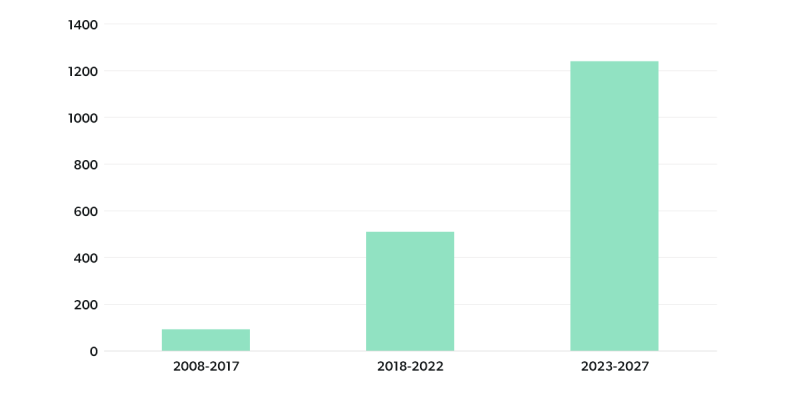

Ahead of the first IPL tournament in 2008, Sony acquired the IPL TV Rights for the first 10 seasons of the IPL for $918m. This equated to around $1.5m per game for the first decade of play. In September 2017 Star India, a subsidiary of 21st Century Fox, acquired the IPL’s global broadcast and digital rights ca. $2.6bn for the subsequent five seasons (2018-22), equal to $8.5m per game and representing an increase of more than 4.5x on the previous deal. The uplift was a clear indication of the success of the IPL product, and for the first time, the rights for a single IPL match were worth more than an India home international match. In June 2022, the BCCI concluded its bidding process for the next 5 seasons’ (2023-27) media rights cycle and sold the rights to Star TV (incumbent), Viacom18 and Times Internet for a combined $6.2bn, or $16.8bn per match.

The value of IPL media rights has multiplied since 2017

IPL global broadcasting rights value per annum ($m)

Source: media reports

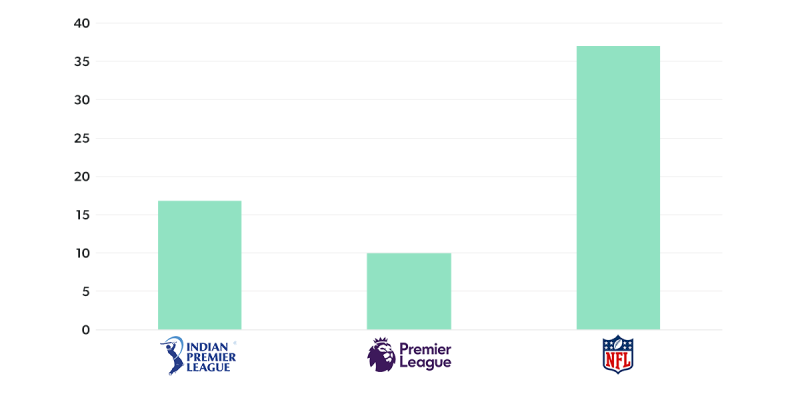

With the new media rights contract in place, from 2023 onwards the IPL will be the second most valuable media rights property in the world (after only the NFL) on a per-match basis at $16.8m.

Only the NFL commands higher revenues per match than the IPL

Broadcasting rights value per match, latest deal agreed ($m)

Source: media reports

Soaring club values

With the dramatic increase in the value of broadcasting rights for the IPL, there has been a similarly impressive rise in team values. When the competition began, the BCCI auctioned the eight new franchises with a minimum reserve price of $50m each, ultimately collecting a total of $723.6m (an average franchise fee of c.$90.4m). Initial owner groups primarily consisted of wealthy Indian families and Indian conglomerates.

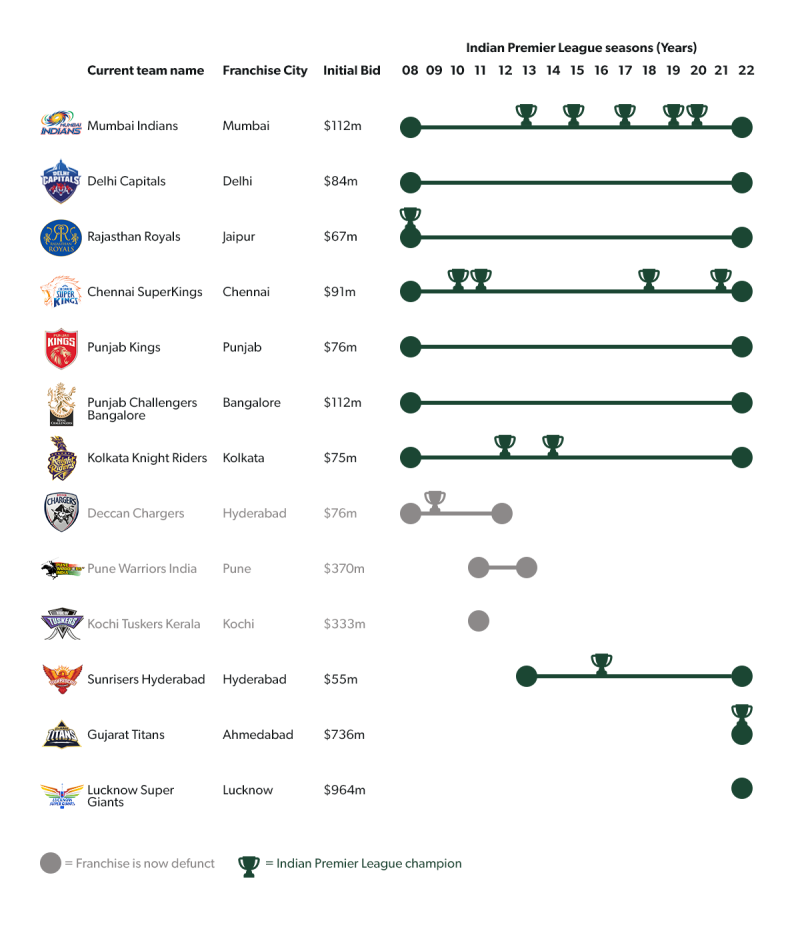

After the first three seasons, the BCCI held successfully held an auction process for two expansion franchises in March 2010, raising a combined $703m. The Pune franchise was acquired by The Sahara Group for $370m and the Kochi franchise by a consortium for $333m. These significantly elevated franchise fees (up nearly 4x vs. the initial auction average) were seen as a testament to the IPL’s success and prospects. However, both these franchises were short-lived and were eventually discontinued in 2012 (Kochi) and 2013 (Pune), and the total number of franchises was back down to eight and stayed this way until the most recent season. In 2012, the Deccan Chargers were replaced by the Hyderabad Sunrisers, who were owned by SUN Group, an Indian media conglomerate.

In 2021, The BCCI ran a closed auction process for two new expansion franchises that would first participate in the 2022 season. The successful bidders for were CVC Partners ($764m for Ahmedabad franchise) and RPSG Group ($964m for Lucknow Franchise), around 9.5x the original franchise auction average.

IPL franchise fees have increased significantly since the original auction in 2008

IPL franchises, fees and active seasons