In this most unusual of years, there has been much speculation on how football’s transfer market – one of the most criticised aspects of the modern game – would respond to the financial constraints imposed by Covid-19.

In a world of unprecedented health crisis, economic downturn and rising unemployment, we might expect the wealthy clubs of European football to be mindful of a potential public backlash if they spend tens of millions on a rising 18-year-old starlet. Perhaps the bigger question is whether those clubs can afford to burn through precious cash piles as profits plummet, even accounting for the ability to pay in tranches and a likely reprieve on FFP. As this shorter-than-usual transfer window nears its close, we look into a topic that might become more of a concern for clubs whose ability to spend freely in the player market has been constrained by revenue losses and reduced cash flows: value for money.

There have been a number of transfer market highs in recent seasons. The records for most expensive goalkeeper, defender and midfielder have all been broken since Summer 2018, with the signings of Kepa Arrizabalaga (moving from Athletic Bilbao to Chelsea for a reported €80m), Harry Maguire (Leicester to Manchester United, £80m) and Philippe Coutinho (Liverpool to Barcelona, £142m) all being set since January 2018. This Summer window, while Chelsea have topped a £220m spree with the £72m capture of Bayer Leverkusen’s Kai Havertz, overall Big 5 expenditure is down around 40% on 2019 - strong evidence of a need to tighten the purse strings at European clubs.

Value for money is subjective of course, but Transfermarkt at least has a methodology for calculating a player’s market valuation which is applied consistently across global football. To determine how clubs have fared in their transfer dealings, we looked at every player’s valuation at the time of a move into or out of the clubs in the Big 5 over the past three seasons and compared it to the fees quoted for the purchase (from the same source). The results were enlightening. We also looked at how clubs fared when selling off assets, and then took this a step further with some further analysis into the differences between playing positions and larger vs. smaller clubs.

Are Premier League clubs being ripped off?

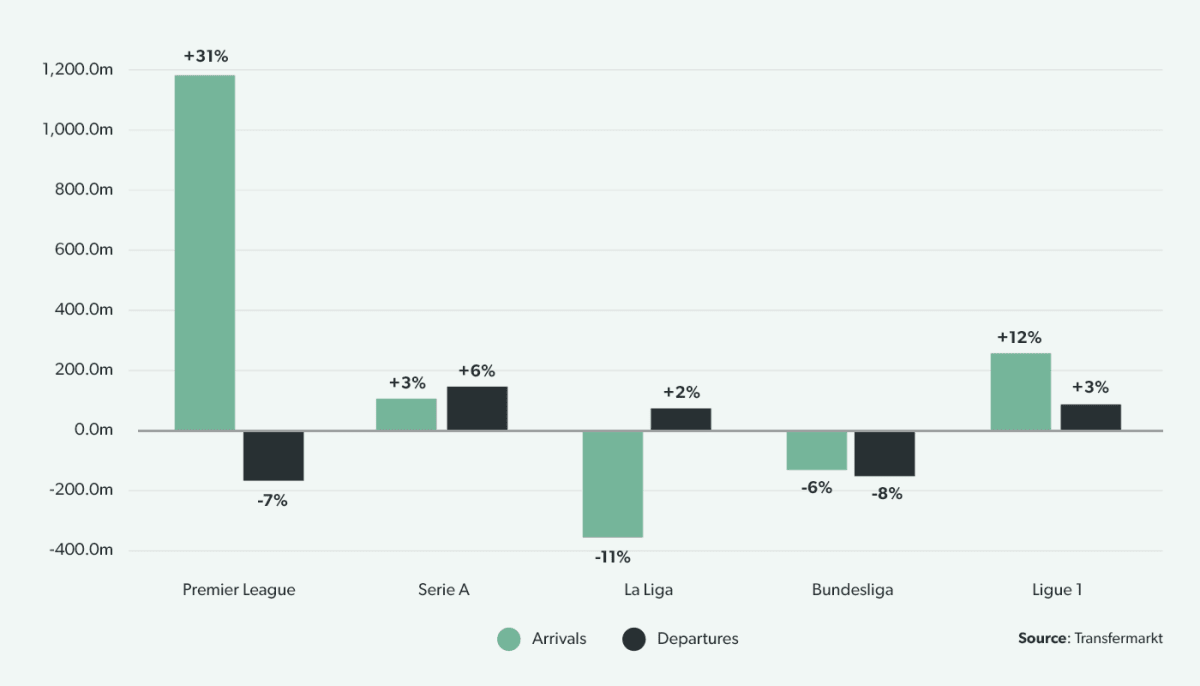

It is well known that the Premier League is the wealthiest league in Europe. But it seems this status does come with a downside, as selling clubs (and player agents) know they can push for a higher price than when selling to less wealthy clubs. Indeed, across the 2017/18 to 2019/20 seasons Premier League clubs collectively spent almost €1.2bn more than the collective valuation of incoming players, an average premium of +31%. Clubs in the Premier League also sold players on at a 7% discount to valuation, leaving more than €150m on the negotiating table over the three year period.

At the other end of the scale, La Liga’s clubs are the transfer masters, acquiring players for 11% under valuation on average (and saving €350m in the process) – and then selling players on at a premium to valuation totaling €75m (+2%) over the three years. Serie A clubs do pay slightly over the odds for players (+3%), but this is more than offset by selling at a premium of +6% to valuation, while Ligue 1’s overspend is second to the Premier League at +12% - driven in no small part by PSG’s transfer activity – and is only partially offset by selling at a premium of +3%. In the Bundesliga, players are acquired at an average 6% discount to valuation but are sold on at a slightly higher average discount of 8%.

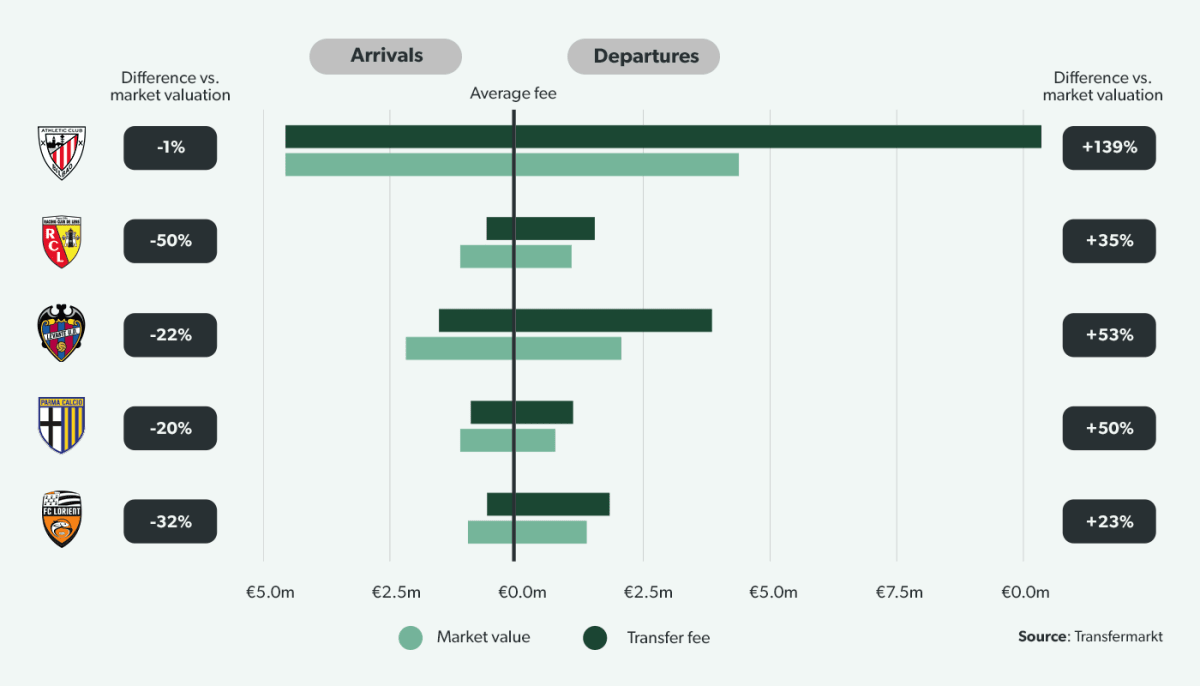

Getting more for less: the top club negotiators

Across the Big-5 leagues, many clubs benefit from transfer income as a key revenue stream alongside broadcast, matchday, and commercial. Aside from developing Academy players to sell, some clubs have traded very effectively on the player market. Atletico Bilbao of La Liga bought players more or less at market valuation but sold them on at the highest premium in Europe of 138% (including the aforementioned Arrizabalaga to Chelsea). Elsewhere, Ligue 1’s RC Lens took top spot for negotiating player acquisition fees with an average discount to valuation of 50%, while Spain’s Levante and Italy’s Parma Calcio 1913 were particularly canny in the selling stakes, both clubs moving players on at an average premium of +50% or more.

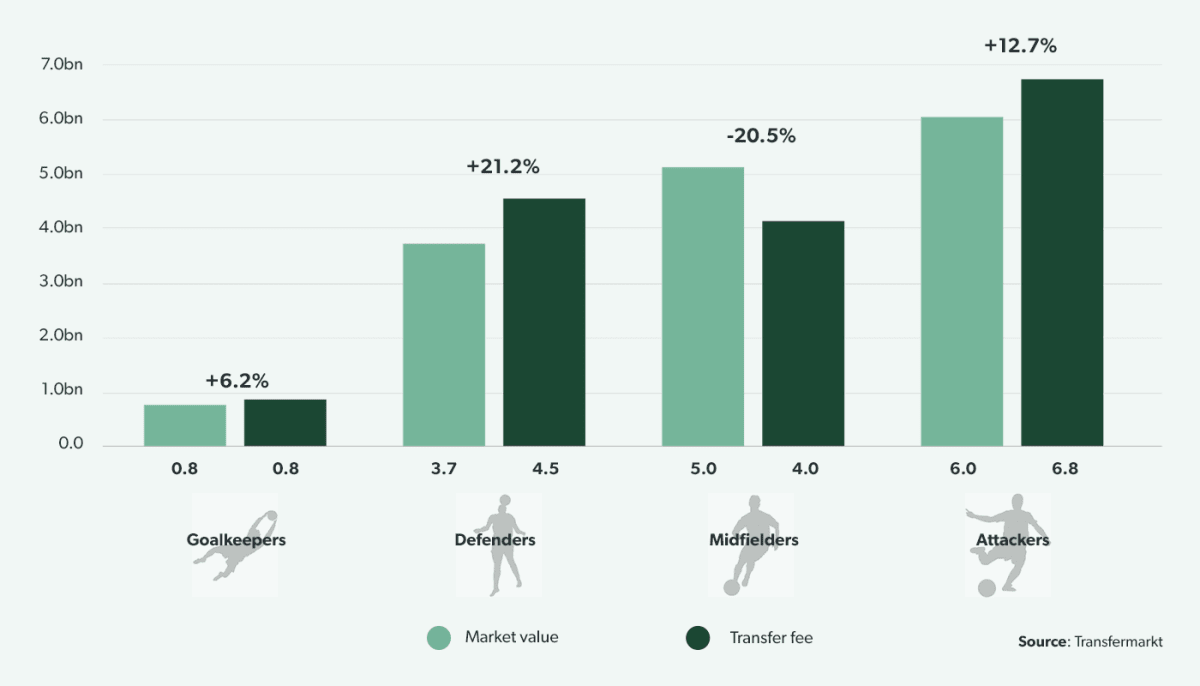

Defenders becoming the premium assets

Perhaps the most surprising insight to come from the analysis was that the highest premium over valuation (+21%) over the last three full seasons was paid for defenders – although with Virgil Van Dijk, Harry Maguire, Lucas Hernandez, and Mattijs de Ligt all making record-breaking transfers in the period it starts to make sense. A strong defence is increasingly seen as a key ingredient for success in the high-scoring modern game – as exemplified by the rise of Liverpool following the additions of Alisson and Van Dijk, and clubs are starting to place higher importance on recruiting quality into a position where truly exceptional players seem more and more difficult to find.

Perhaps the most surprising insight to come from the analysis was that the highest premium over valuation over the last three full seasons was paid for defenders

Attackers are always prized assets, of course, and it is no surprise to see that they commanded a 12.7% premium over valuation. Meanwhile, goalkeepers were also more valued than historically with the likes of Arrizabalaga and Alisson making €70m+ moves. Relatively speaking, there were fewer “blockbuster” deals for midfielders (Pogba moved before the three-year period in question, and Havertz afterwards) and better value for money has been achieved in this position: midfielders were acquired at an average discount to market valuation of 21%.

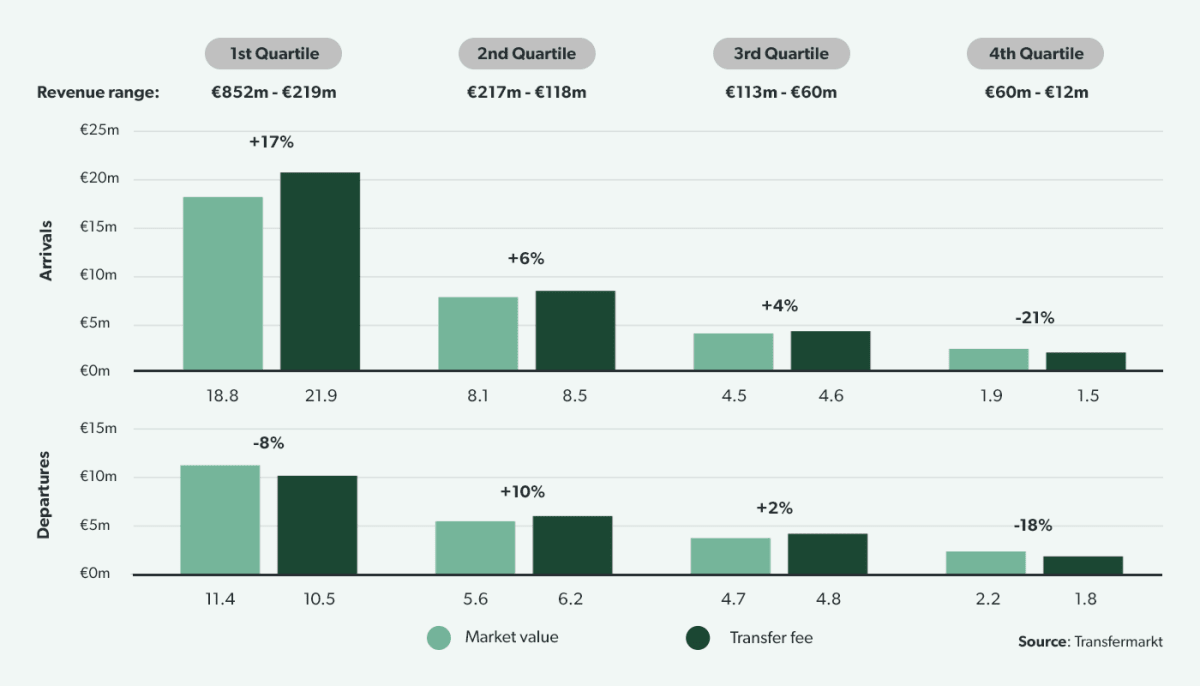

Biggest isn’t best: the anti-economy of scale

As the wealthiest European league pays the highest premium for players, so too do the wealthiest clubs relative to their peers. The chart below shows clubs sorted into four quartiles by size of revenue (data from accounts for the 2018/19 financial year). On the player acquisition side, the pattern is very clear: the bigger the club, the higher the premium paid. Indeed, the smallest clubs in the Big 5 pay on average 21% under valuation in the transfer market, presumably because selling clubs and agents know there’s little point pushing for more. When it comes to selling, the pattern isn’t quite the same, although we do see that the biggest clubs get a poor deal when moving players on, receiving fees around 8% lower than valuation on average.